Defining student rights inside and outside the schoolhouse gate

Current social, political events have blurred the line for student rights

March 16, 2018

With a polarized social and political climate, more and more of us have been challenged to speak up and use their voices. Whether it’s in school or on social media, students have been coming together and rallying for change. However, the responses to these actions from both peers and adults have ranged from supportive to discouraging. As we find our rights to organize walkouts or kneel on a football field challenged, the question of what our rights as students truly look like has been raised. The answer may be unclear, but students are guaranteed rights to privacy, speech, petition and press by the Constitution — to a certain extent.

Throughout this section, you’ll find an overview of what your rights as a student look like and how students have been exercising these rights throughout history.

As you begin to stand up and speak out, we hope this section gives you a good idea of how you are protected by law to take action and feel empowered to do so.

Assembly

Since the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida that killed 17 students and faculty members on Wednesday, Feb. 14, students all over the nation have been organizing school walkouts in attempts to call for legislative action in relation to gun control. These protests administered and carried out by students have fostered the question: what rights do students have to protest in school?

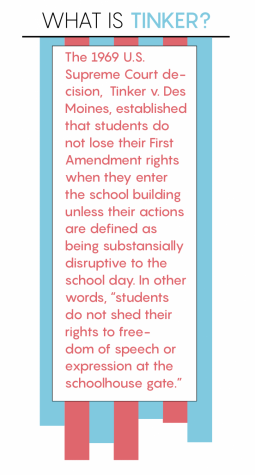

In the First Amendment, citizens are given the freedom to assemble or petition peacefully. For students in public schools, this same freedom is upheld within the school building except when an action is defined as a substantial disruption to the school day. This freedom was set in the landmark Supreme Court case, Tinker v. Des Moines in 1965, in which students protested the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to school.

However, administrative responses to student protests may vary. For example, with talk of school walkouts or protests by students across the nation in the wake of the Parkland shooting, some school administrations have recognized student rights to assemble and petition. Some others, though, such as Needville Independent School District in Needville, Texas, have threatened students with disciplinary action such as suspension.

However, administrative responses to student protests may vary. For example, with talk of school walkouts or protests by students across the nation in the wake of the Parkland shooting, some school administrations have recognized student rights to assemble and petition. Some others, though, such as Needville Independent School District in Needville, Texas, have threatened students with disciplinary action such as suspension.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, since it is required by law for students to attend school, school administrations may technically discipline for students for voluntarily missing class. However, any disciplinary action taken by administration must be due to the unexcused absence of the student rather than the fact that the student is protesting.

Both Mill Valley and De Soto High School students coordinated school-wide walkouts on Thursday, March 8 in support of the students and teachers that lost their lives in the Parkland shooting. According to freshman Ellie Boone, who helped to organize the event, a student’s right to participate in a protest like a walkout is important.

“I guess people kind of undermine students a little bit. People say ‘leave it to the adults to take care of things; you don’t understand at such a young age,’ but I feel like even now, we understand even more,” Boone said. “High schoolers are where the school shootings are taking place, so it’s even more relevant to us and it’s important for us to take a stand rather than an adult who hasn’t been through that.”

Previously, speech teacher Annie Goodson personally witnessed the power of student assembly and protest after the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, when her students at Junction City Middle School decided to wear black hoodies and keep their hoods up during the school day.

“The administration really had to think: yeah, wearing a hoodie is technically against the rules but is that really a battle we want to fight? Are they being disruptive? Are they preventing others from learning?” Goodson said. “Ultimately, the answer to that was no. So the kids had a day where they wore hoodies and it was actually pretty powerful.”

More recently, Lawrence High School students hosted a sit-in protest at their school during school hours to call for administrative action when student athletes mocked transgender students in a group chat. Around 100 students exercised their right to protest, and eventually met with administrators to discuss what they hoped the sit-in would accomplish. Like the instance Goodson witnessed in Junction City, LHS administration allowed students to peacefully protest.

Ultimately, the namesake of the Tinker v. Des Moines case that allowed these students to exercise their rights, Mary Beth Tinker, said she encourages students to utilize their right to protest.

“This is one of the many strengths of young people,” Tinker said. “You feel things, at an emotional level. You haven’t been calcified yet, or immune to the feelings. When you see something, you’re going to feel it. And that’s how we felt, when I saw those images I felt very emotional like those kids in Florida or kids all over the country now. And that’s a very powerful motivator, especially combined with examples of people standing up and speaking out about it.”

Speech

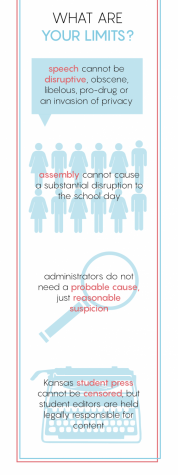

Like a student’s right to protest, student free speech rights are also partially restricted within the school building. Although a student still maintains their First Amendment rights in school because of Tinker, student speech may be censored if speech is defined as disruptive to the school day, obscene, slanderous, pro-drug or an invasion of privacy.

According to University of Kansas professor Mark Johnson, who teaches First Amendment law, student free speech rights before the Tinker v. Des Moines doctrine was established were murky since “there wasn’t really any idea on how the First Amendment dealt with student rights.”

Since Tinker, though, some court cases have restricted student free speech rights, like the 2007 Morse v. Frederick case where a student displaying a “Bong hits for Jesus” banner was suspended for promoting drug use, and the 1986 Bethel School District v. Fraser case that established that lewd or obscene speech was not protected by the First Amendment.

Within school, Goodson believes that allowing students free speech rights in classes like Debate is imperative to their growth as a scholar.

“Kids have to be equipped to articulate themselves and there are very few classes where we not only teach kids how to disagree,” Goodson said, “but encourage them to disagree and say ‘here are some ways where you can process and make your case.’”

Senior Madeline Myrick agrees, and said practicing free speech inside and outside of school helps students prepare for life after high school.

“If we are suppressed in high school, there is nothing that will help us when we want to express our own opinions,” Myrick said. “We’ll just end up creating a society that doesn’t know how to express a decent opinion without wanting to cause dissension.”

Likewise, Goodson said free speech rights empower students.

“Talking about stuff and articulating things helps you kind of realize who you are as a person,” Goodson said. “Aristotle said that saying something makes it true; saying something is important because words have value. If we don’t give kids the opportunity to say things, then we’re kind of limiting their truth.”

However, student speech rights sometimes become blurred with the advent of social media. According to Johnson, school administrators may discipline students for posting content that is not protected by free speech law if the student posts while on campus. Student social media activity that is administered off-campus, though, is sometimes gray.

“By and large, as long as you’re not doing things like trying to bully teachers, the school can’t really stop you from doing anything [off-campus],” Johnson said via phone. “You have to draw a distinction between what you can do and what you should do. You may have the right to do certain things at home, but that doesn’t mean you should do them.”

Social studies teacher Angie Dalbello said that in the end, giving students the right to speak freely within the school building strengthens their education.

“I think that part of being in school is being able to communicate effectively and listen to other people and their opinions and share those opinions and talk about them,” Dalbello said. “You have to have a lot of leeway in what you can talk about if kids are going to be able to think for themselves and effectively communicate in life.”

Privacy

A student’s right to privacy within the school building was restricted in the 1985 Supreme Court case New Jersey v. T.L.O., establishing that a student may be searched in the school building if administration has reasonable suspicion that the student is violating the law or school rules.

In the case, a student was suspected of having marijuana in her purse and was taken to the principal’s office, where her purse was searched. When the student claimed that this action violated her Fourth Amendment rights, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that “students have a reduced expectation of privacy when in school.”

According to School Resource Officer Mo Loridon, the school handbook states that principal Tobie Waldeck would need reasonable suspicion in order to search a student. Since all students sign the student handbook, they are all held to the standard

that “anything brought onto campus is subject to search: your purses, your backpacks, your lockers and even your cars.”

Off campus, though, Loridon said students have full access to their full Fourth Amendment rights,

which state that law enforcement has to have probable cause or a search warrant in order to search people. Probable cause is different from reasonable suspicion as it requires either evidence, admittance or consent.

Within the school, Loridon said there are situations where he puts student safety above student privacy.

“In the matter of safety, I will violate anyone’s Fourth Amendment rights,” Loridon said. “If you come to me and say Jimmy has a gun, I’m not going to worry about probable cause. I’m just gonna go. And I’m going to take his backpack or do whatever I need to do, because my number one job here, and Mr. Waldeck’s, is to keep students safe.”

Dalbello agrees, and emphasizes the fine line between protecting student rights and protecting students.

“The minute that you walk through the schoolhouse gate, all of your rights are diminished to some extent,” Dalbello said. “So, it’s the balance of giving you as much privacy as we can afford you but at the same time balancing that out with everyone’s safety and security.”

As a whole, junior Madelyn Lehn believes that privacy is a critical aspect of student rights both inside and outside of the school building.

“Even if you don’t have anything to hide, you’re still entitled to your own privacy which is important to understand in all areas of life,” Lehn said. “Not just at school.”

Press

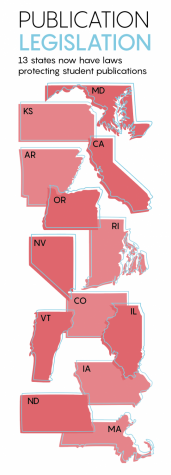

The Supreme Court decision in the 1988 Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier case ultimately established the right of school administrators to censor student publications in instances where administrations deem content “inappropriate.” However, since the decision, 13 states — including Kansas — have passed laws overriding the Hazelwood decision and giving rights to student journalists in their state.

Passed in 1992, the Kansas Student Publications Act protects student publications from any administrative censorship, even when content may be “political or controversial,” given that content is not libelous, obscene, or encourages illegal behavior. Additionally, the act states that student editors are entirely responsible for their publication, and protects journalism advisers from being fired if controversial content is published.

For the 37 other states that don’t have protections like ours, though (including our neighboring state of Missouri), student publications are still subjective to censorship. However, the New Voices Movement, a program sponsored by the Student Press Law Center, has recently spurred a national movement to pass more laws that protect student journalists; since 2015, six states have passed laws like Kansas’s.

Although Missouri has previously introduced past New Voices legislation in the past few years, it has failed to pass through the state’s Senate. Currently, though, a new version of the bill has passed the House of Representatives and is slated to be reconsidered by the Senate.

Although Missouri has previously introduced past New Voices legislation in the past few years, it has failed to pass through the state’s Senate. Currently, though, a new version of the bill has passed the House of Representatives and is slated to be reconsidered by the Senate.

Senior editor-in-chief Camille Baker at Kirkwood High School in Kirkland, Missouri recently testified in front of the Missouri House in support of the bill, and said that she wanted to emphasize the power of student journalism in her testimony.

“If you have an opinion you are completely entitled to it, and you are able to push your voice out regardless of the norms or if it’s controversial at all,” Baker said via phone. “That’s just a really empowering thing as a student. Being in high school, you’re limited to the confines of a classroom where you’re just listening to an adult speak everyday, and you’re just told black and white, this is what to do everyday. So when you’re able to take your own thoughts and put that on paper, that’s something that’s super empowering.”

Kirkwood’s journalism adviser Mitch Eden agrees with Baker, and said that if passed, legislation protecting student journalists would in turn “protect that minority opinion and make everyone feel like they have a voice.”

Although Baker and Eden said that the administration at Kirkwood is supportive of the school’s journalism program and does not exercise their Hazelwood right to censor student publications, Eden said that he has worked at Missouri schools that haven’t always been so lucky.

“The first ten years of my career, I worked at Oakwood High School, and for the last five of those years, my kids were on speed-dial with the SPLC [Student Press Law Center],” Eden said via phone. “The principal did not really care for what they were covering. What I see happening in other schools is that the advisor is either apprehensive about it or scared to allow that because of their job or they’re just not knowledgeable about the law. That happens too often, where the kids say ‘we could never do it’ or the advisor says ‘no, we shouldn’t be doing that’ and everyone just gives up.”

In Kansas, though, students across the state have utilized their right to publish controversial content without fear of censorship. Most recently, in 2017, six student journalists at Pittsburg High School published a story questioning the credentials of the school’s newly hired principal, ultimately forcing her resignation.

According to Pittsburg journalism adviser Emily Smith, the Kansas Student Publications Act was crucial protection for the student journalists that published the story.

“In Kansas we are lucky to have the SPA. It afforded my students the opportunity to pursue a story that made many adults uncomfortable,” Smith said via email. “At any point, an administrator could have stopped the story. My intuition tells if [we had lived] in Missouri, the story would not have been allowed to be published.”

Closer to home, in 2015, 2016 graduate and former Mill Valley News editor-in-chief Justin Curto published a series of stories covering the recall of Board of Education member Scott Hancock amid sexual harassment allegations. Like Smith, Curto said that the SPA ensured his rights and pushed him to follow the story.

“I think from the start, it helped because we knew we were going to be able to do it,” Curto said. “It was great experience on my part to have to make all the considerations that a real-world journalist would have to make reporting on this.”

The real world experience imparted to student journalists, as well as the depth of content covered by students journalists, is exactly what makes protection like the SPA crucial, according to Johnson.

“Student press is the only alternative voice to the school administration,” Johnson said. “Unless you have that, you don’t have any kind of counterpoint to the school administration’s point of view, and the students don’t have a voice. The students may not get their way, but it’s important that the students can express themselves, so the administration can’t just ignore them.”

Baker said that legislation protecting student journalists is also important for real-world journalism experience.

“We are our nation’s future, so being able to foster a society where we are able to tackle the same subjects that professionals tackle is so important because going into the real world, we need to have that experience,” Baker said. “Within politics, there are so many instances of fake news in the world of journalism that we need to be able to reshape it and mold it into something that is reliable; the only way we can do that is through real life practice.”

With the recent emphasis on student press protections spearheaded by the New Voices Movement, Kansas Scholastic Press Association director Eric Thomas believes that student journalists will soon have full access to their First Amendment rights.

“A few years ago, we would have said the effort to pass these laws is totally dead on arrival,” Thomas said. “Nobody’s trying to do it, nobody wants to try to do it, there aren’t any bills, everybody seems ignoring it. But this seems to be different moment. I feel like a lot of these efforts are percolating up and while they may be coming short of what they need to be, I feel like it is a conversation that is happening much more than it ever did.”