Diabetes affects the everyday lives of staff and students

Due to a side effect of type one diabetes, junior Colin Prosser has to check his glucose levels everyday before he eats. “It’s mostly just around the meal time.” Prosser said. “You just have to test imbolis before you eat and then two hours or so afterwards.”

March 13, 2018

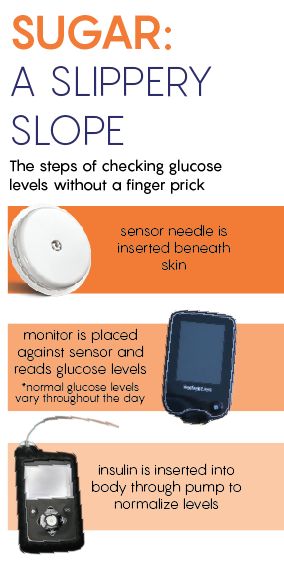

Before sitting down to eat, junior Colin Prosser grabs his glucose monitor and holds it to the sensor on his body. When it doesn’t vibrate, Prosser knows his glucose levels are in the right range. When the monitor does vibrate, though, Prosser’s glucose levels may be too high or low, meaning he may have to dose himself with insulin or eat a quick snack to add sugar to his bloodstream. This routine is part of the everyday reality of diabetes.

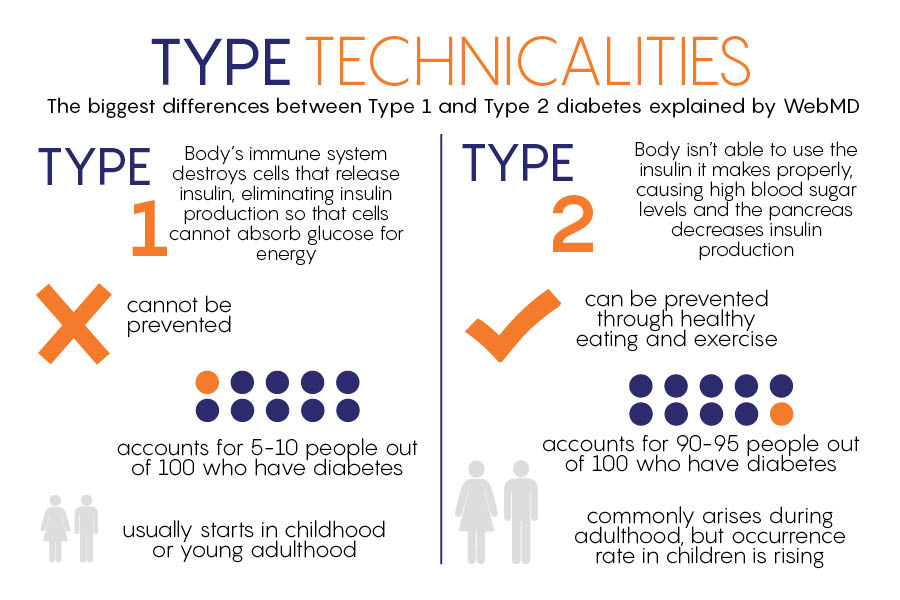

The three prominent subsets of diabetes mellitus are Type 1, Type 2 and gestational diabetes, all revolving around the body’s inability to correctly produce or respond to insulin, a hormone that allows the body to use glucose for energy. With Type 1, as reported by WebMD, the immune system obliterates insulin-creating cells. Type 2 is different in the sense that the body doesn’t make insulin the way it should. Additionally, type two diabetes can occur develop at any age, while type one is more seen in the juveniles.

The three prominent subsets of diabetes mellitus are Type 1, Type 2 and gestational diabetes, all revolving around the body’s inability to correctly produce or respond to insulin, a hormone that allows the body to use glucose for energy. With Type 1, as reported by WebMD, the immune system obliterates insulin-creating cells. Type 2 is different in the sense that the body doesn’t make insulin the way it should. Additionally, type two diabetes can occur develop at any age, while type one is more seen in the juveniles.

After getting the flu in fifth grade and experiencing an irregular recovery, Prosser found out he had Type 1.

“I was very dehydrated a lot,” Prosser said. “At the same time, I would drink insane amounts of water and still be dehydrated and go to the bathroom a lot. Also, I didn’t have any appetite. Obviously, that was a sign that something was wrong because a fifth grade boy should be eating a lot.”

Similarly, English teacher Mike Strack was diagnosed with Type 1 in February 2003. He said he had similar symptoms, like extreme dry mouth and sudden, significant weight loss. To keep their glucose levels healthy, both Prosser and Strack use an insulin pump, a device used to control blood sugar levels.

“The pump allows me to eat more things that I really shouldn’t eat,” Strack said. “I can enjoy or eat what I want without having to worry as much. So, really it just simplifies everything.”

However, not everyone with diabetes needs to watch their glucose levels. Others, such as senior Abby Sutton, monitor water intake. Diabetes insipidus (DI) is a water-based diabetes caused by a hormone imbalance from the pituitary gland. Sutton said she struggled with dehydration and urination issues for about six months before she was officially diagnosed with DI in February.

“I just have to drink a lot more water than I’m used to because if I don’t then I get a very bad migraine and I get very light-headed,” Sutton said. “It’s just hard because some teachers don’t understand that’s what I have.”

According to school nurse Heather VanDyke, nurses begin to give students with diabetes more control as they grow older in an attempt to teach students how to manage their diabetes on their own.

“[In elementary school] we’re really watching every carb they take in,” VanDyke said. “In middle school we’re trying to give them a little bit more [independence] and by high school I don’t see a lot of them much at all.”

Because Sutton needs to consume about two gallons of water per day to keep up with DI, she says her appetite has gone down.

“My stomach gets filled with water because I drink so much,” Sutton said. “I haven’t gained any weight from this. I should be gaining weight because I’m growing.”

Oftentimes, with the two types of diabetes mellitus, Strack has noticed the general public can make assumptions about the condition, specifically concerning the differences between the types and their different causes.

Oftentimes, with the two types of diabetes mellitus, Strack has noticed the general public can make assumptions about the condition, specifically concerning the differences between the types and their different causes.

“I think to hear you’re diabetic is often [identified] with certain poor health habits or poor eating habits,” Strack said. “Type 1 diabetics don’t really know why [their bodies] stop producing insulin. I think [people] may have an idea that someone’s weight impacts [type one diabetes].”

Throughout his experience with diabetes, Prosser feels he’s emotionally matured quicker than he normally would have.

“I was usually a responsible kid,” Prosser said, “but it definitely makes you step up your responsibility level because it’s your health and not just doing chores.”

VanDyke believes her responsibility to students with diabetes is to prepare them for the transition between supervision as students and independence as an adult.

“[They] really understand and accept [diabetes] before they leave.”

Despite the precision required to keep himself healthy, Prosser doesn’t believe his disease stops him from participating in everyday activities.

“You can obviously work within it to do whatever you want, and you can eat whatever you want,” Prosser said. “[Diabetes is] not something that limits you.”