Diversity at Mill Valley

An in-depth look at many aspects of life for minority students throughout the school

February 19, 2020

Demographics

A graphical depiction of the school, county, state and nation’s demographics by race

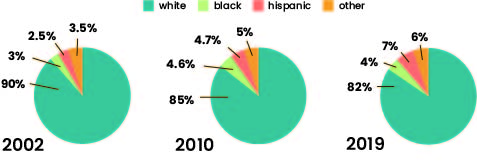

Each year, every public school in Kansas must publish basic information about its student body, including the breakdown of certain racial groups. The school’s percent of no-white students has increased by almost 10% since the school opened in 2000. Sources: Principal’s Report & Kansas Building Report Card 2018-2019.

Results from the 2019 census of different racial groups shows Mill Valley closely mirrors the state of Kansas. Source: United States Census Bureau

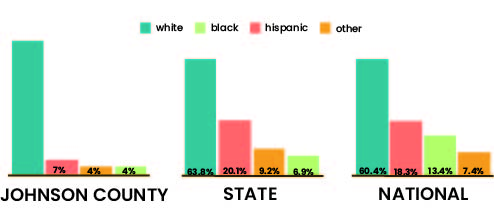

Participants were asked to recall a time they had experienced racism within the school or community.

Sophomore Drew Morgan shares his personal story

Morgan sheds light on how racism and stereotypes have impacted his life

An elderly, white man approached the baseball field concession stand. He stopped to stare at sophomore Drew Morgan who was busy preparing a large order of Icees. After finishing his task, Morgan greeted the man and apologized for the wait.

“You’re lucky your people are allowed to work here,” the man said.

Ignoring the comment, Morgan asked again how he could help the man.

“Back in my time, your people wouldn’t even be allowed to be in this certain section,” the man said.

Not wanting to lose his job, Morgan replied that he couldn’t help the man if that’s all he was going to say. Without another word, the man walked away.

This blatant racism was not the first time Morgan’s African American ancestry played a role in how people treat him. Adopted into a white family, the color of his skin began shaping his world before he even understood what race was.

“I remember when I was growing up … a lot of people would stop and stare at my family in public, and it was something that I didn’t understand at the time,” Morgan said. “[I thought], ‘Why are they staring at me?’ I was just staring at my parents.”

While Morgan recollects the discomfort that dominated these moments, he recognizes that it’s natural for people to do a double-take when they notice his family’s unique dynamic.

Exiting the gym floor, sophomores Drew Morgan and Caelia Hissong finish playing the game.

Race grew to be a larger aspect of his identity upon entering grade school and not always in a positive way; Morgan often felt disconnected from his white peers who didn’t share the same race-related experiences that had become increasingly prevalent.

He feels these problems have been partially alleviated since he started high school. The increased diversity allowed him to find students who are “really vocal about how they feel about being black, how they feel about how they’re treated.”

However, Morgan is no stranger to the notorious history class situation that countless black students experience throughout their education: the room full of non-black students that inevitably turn toward the single black student when it’s time to discuss the Civil War or the civil rights movement. While Morgan doesn’t blame others for this reaction, he sheds light on why this kind of occurrence creates an unpleasant environment.

“A lot of people will turn around and look at me or turn toward me,” Morgan said. “It’s extremely uncomfortable for me. It’s just a lot of eyes on you for something that you can’t really control.”

Morgan also hears malicious comments made at school based on racial stereotypes stereotypes tied to black people.

“There’s a good amount of people at Mill Valley who, whether it’s a joke or not, say ‘black community: there’s crime, criminals, a lot of just violence.’ I think that’s what a lot of people like to push as a stereotype that we’re a violent community of people,” Morgan said. “I’ve also seen some people say we’re ghetto, that we’re not educated well enough, [and] that we can’t speak proper English.”

A stereotype that Morgan is especially bothered by is that black people are inherently more violent than white people. Morgan thinks this ill-founded stereotype is exacerbated when people only look at shallow statistics and don’t address underlying causes behind those issues.

“[The stereotype] that all black people are ghetto… kind of irks me a little bit, because there are a lot of black people who don’t act ghetto. No one wants to act ghetto; it’s the situation that they’re in,” Morgan said. “A lot of people don’t grow up in great places … in order to cope with that, they get into violence. And it’s not the right thing to do, but it’s the only thing they know.”

While high school was a step up in terms of racial diversity within the student population, which allowed him to interact with peers who he can speak to about these problems, this doesn’t mean it’s always easy. Going to a school with a primarily white staff has limited the number of adults in Morgan’s life that are fully capable of understanding these race-related aspects of his life.

“It’s a little bit hard because when you’re trying to explain a situation that you’re going through, or something that’s happened to you in school, or maybe someone’s saying something,” Morgan said. “It’s hard for them to put themselves in your shoes, and vice versa.”

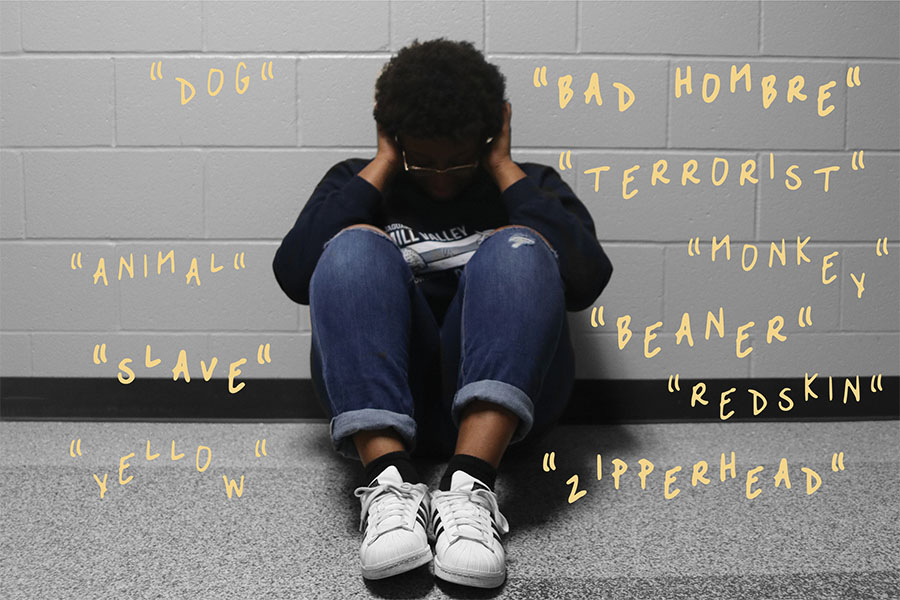

Racial slurs and derogatory remarks have a long-lasting impact on people of all races and ethnicities and can lead to increased tension within society.

Students and administration face racist language within the classroom

Minority students continue to be impacted by the prevalence of racist slurs at school despite current consequences

While sitting through another day of AV Production Fundamentals last year, junior Beth Desta got into a heated argument with a boy sitting next to her in class.

Desta doesn’t remember what instigated the conflict. What she does vividly recall, though, is the boy’s response.

“He disagreed with me. He just looked at me in the eyes and called me the n-word,” Desta said.

According to Desta, the use of racial slurs, including the n-word, is commonplace at Mill Valley. In her experience, white students callously use the word while joking with their friends or singing along to popular songs, while they lack an understanding of the deep racist roots of the word — or meaningful consequences for its usage at school.

While Desta described principal Tobie Waldeck as extremely upset about the incident, the student who called her the n-word to her face received two days’ in-school suspension, which proved to her that “the administration doesn’t really care.”

Sophomore Ryan Lucas shares Desta’s disappointment in the school’s response to the use of racist slurs at school. After a student in Lucas’s World History class called her the n-word and Lucas reported it, the student received a three-hour detention. To Lucas, the punishment was woefully inadequate.

“With all the history of that word, with slavery and Jim Crow and all of that, it should have been a lot more than just a three-hour detention,” Lucas said.

Desta shares her disappointment regarding the inconsistency and lack of severity in the school’s punishments for racial slurs, referencing a black student who received two days of out-of-school suspension. Desta’s harasser received only one day of out-of-school suspension, and Lucas’s received zero days of out-of-school suspension.

“I just don’t think they handle it seriously enough when it comes to non-black people saying the n-word. A black kid got suspended for even longer for saying it,” Desta said.

Assistant superintendent Alvie Cater disagrees with Desta’s assertions of unfairness and believes that the district already strongly opposes racial harassment at school.

“USD 232 will not tolerate racial slurs in our schools, on school property, or at school-sponsored activities. We want all schools to be safe places for each student so they can focus on learning and doing their very best,” Cater said. “Students have enough to do without having to worry about insensitive and inappropriate behavior on the part of others.”

Cater notes that the consequences for using racial slurs are determined by the principal based on “the student’s age and maturity, the nature and seriousness of the infraction, the student’s previous disciplinary record, and any other relevant factors.” He also explains that consequences for the use of racial slurs can range from a detention to a long-term suspension.

While the claim that white students who use racial slurs are punished too lightly is disputed, the harm the slurs cause to minority students cannot be understated. After she was racially harassed, Desta wanted to transfer.

“After that, my mindset was, ‘Mill Valley is racist. Mill Valley is racist. Everyone here sucks,’” Desta said. Even when Desta isn’t individually attacked at school, the atmosphere of rampant racist language and attitudes hurts her.

Even when Desta isn’t individually attacked at school, the atmosphere of rampant racist language and attitudes hurts her.

“I come back from school in a bad mood most days. There are some days where I come to school in a good mood, and I also leave in a good mood,” Desta said. “There are other times where it’s like, even if no one’s saying anything to me, or to anyone, in a derogatory way, it still kind of hits. It’s still like, ‘Okay, this is the school I go to where people don’t know or understand their limits.’”

Lucas believes that despite the prevalence of racist language at Mill Valley, the school hasn’t taken enough steps to raise awareness about the issue; to her, that’s something that needs to change.

“There definitely needs to be some type of awareness. It should be common knowledge not to use the n-word,” Lucas said, “I don’t understand why it’s not, especially with all the history behind it.”

Desta agrees; in fact, she blames the school’s failure to raise awareness for the rise of racist language.

“People just say it to say it at this point. Whether it’s in a song, or just saying it to their friends, or saying it as an insult to either another white kid or another minority student,” Desta said. “People just don’t really think about or understand what it means because the school doesn’t do anything to show them that.”

Cater does agree that more progress always needs to be made in creating a more inclusive school community.

“We believe that USD 232 must continue addressing diversity and inclusion to support the best possible learning environment,” Cater said.

Desta thinks that what’s taught in classrooms is part of the problem. She says that a friend of hers from the Kansas City school district, which is 11% white, receives much more education about non-white people and cultures; this proves to her that a diverse curriculum is possible.

“The administration needs to do a better job of teaching kids what needs to be taught, and not just what they think should be taught,” Desta said. “We learn about Christopher Columbus, but we don’t learn about Malcolm X. I think that’s one of the biggest problems here.”

While Kansas’s high school U.S. History curriculum includes Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party in its standards, a teacher said that the activist is only mentioned “peripherally” in their class. Within the department, the level of education on black history varies; a student in Aaron Cox’s U.S. History class said they learned about Malcolm X, while a student in Michael Bennett’s U.S. History class said the name didn’t come up.

Use of racial slurs like the n-word is common in popular culture as well, especially the music industry. Desta believes that, while rappers like Tupac used the n-word powerfully to refer to their black brothers and sisters, modern musicians don’t treat the word with the same respect.

“When [Tupac] was using it, it wasn’t the way that like Migos would use it now,” Desta said. “They make it seem like just like any other curse word out there, because they themselves don’t understand it.”

Another avenue for racist language to work its way into pop culture is through the popular video publishing app TikTok. Famous TikTok user Mattia Polibio recently faced backlash from fans for using the n-word in their videos, and Lucas sees racism constantly on the app.

“I spend a majority of my social media time on TikTok,” Lucas said. “There’s always going to be at least one video that I find on my page that’s blatantly racist.”

Other social media platforms like Instagram are, according to Desta, also hotbeds for racist language.

“People don’t really care about what they say when it’s over a screen. They’ll say the n-word over DM on Instagram but then never talk about in person. They’ll say, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean it,’ or they’ll try and ignore it completely.”

Desta described an online incident where someone responded to one of her Instagram posts with a direct message calling her the n-word. The person then repeatedly commented the slur below her post, then sent her another derogatory direct message.

Lucas has had a similar experience with the prevalence of online racial slurs.

“On the Internet, and even on Snapchat or Instagram, I’ll be scrolling through somebody’s story and somebody who’s white will use the n-word,” Lucas said.

Lucas and some of her black friends attempted to raise awareness about online use of slurs. They all shared a post asking white people not to use the n-word in person or online. However, Lucas didn’t think the posts had any impact.

“We’ve tried [asking people to stop],” Lucas said. “Apparently, it doesn’t work. People are going to do what they want to do.”

The frequency with which Desta sees white people using the n-word upsets her, and she believes other people of color feel the same way.

“It feels to most minorities that the white people have everything. The n-word is just one thing that they can’t have, and they can’t live without it,” Desta said. “There’s no one that says that word more than most white people do.”

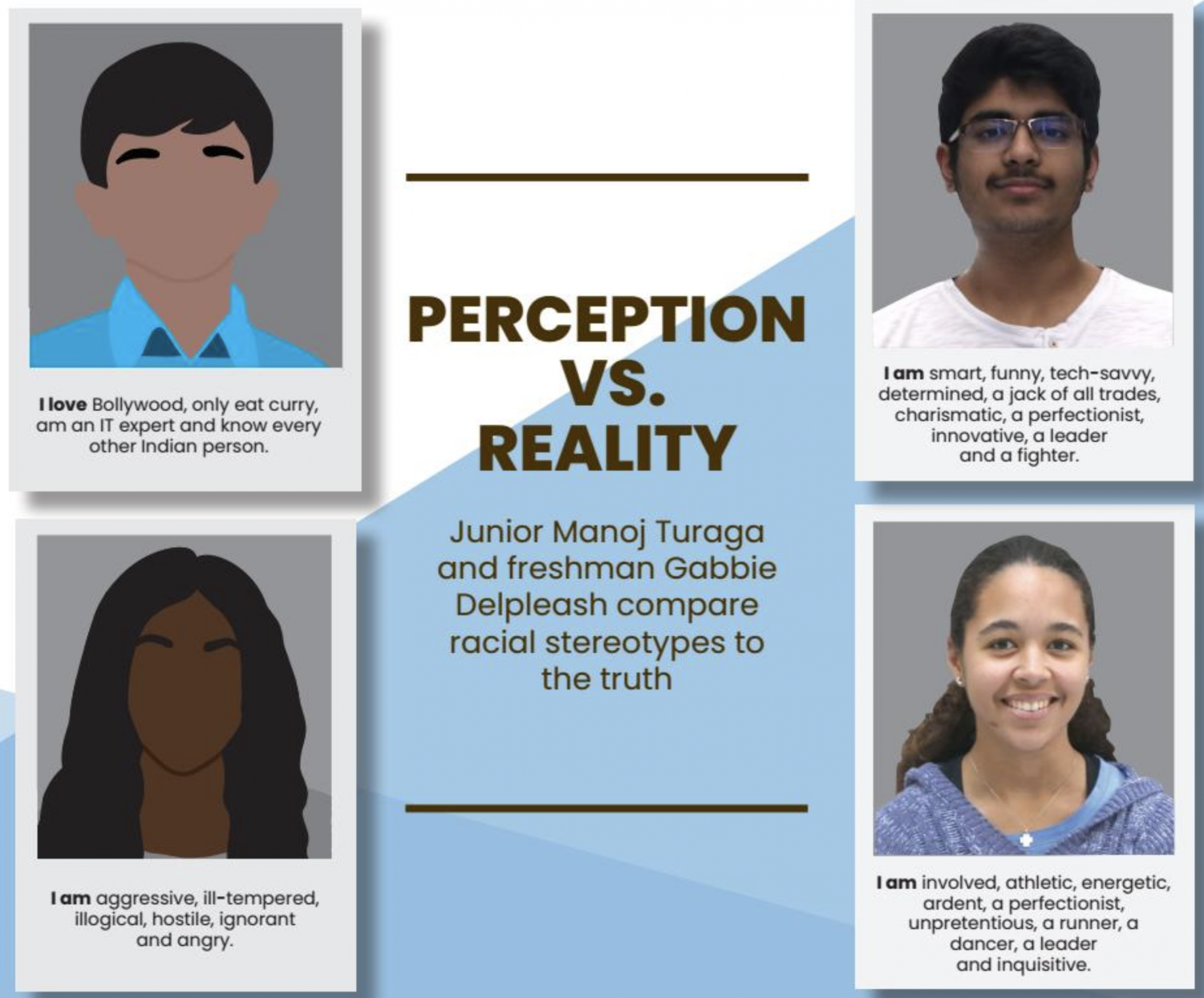

Racial stereotypes are often innacurate representations of individuals. Junior Manoj Turaga and freshman Gabby Delpleash redefine these stereotypes.

The impact of racial stereotypes

Students and teachers address the stereotypes tied to their appearance, culture or ethnicity

Since moving from Puerto Rico to the U.S. when she was four years old, English teacher Coral Brignoni has been unable to escape the stereotypes tied to her race. She may have been born a U.S. citizen, but her dark hair and skin color consistently influence how the world perceives her.

As a major sector of racist remarks and a common reinforcer of discriminatory beliefs, these racial stereotypes can be constant reminders that race remains a source of division between people everywhere. From joking among friends to malicious statements meant to cause pain and exclusion, the ways in which stereotypes affect minority individuals are diverse.

Being Hispanic, Brignoni is often misidentified as Mexican; she hears comments that reflect stereotypes about Mexicans and witnesses the stereotyping of Spanish-speaking countries.

“Mexico and Puerto Rico are two different countries. I always have people ask me if I speak Mexican, or if I like tacos, [but] there’s a distinctly different culture between Puerto Rico and Mexico,” Brigoni said. “They are not even close.”

Brignoni feels that spreading and reinforcing this kind of inaccurate stereotype can put a negative lense over how people view each other.

“Stereotypes lead human beings to make assumptions about other people,” Brignoni said. “So that would be my biggest caution, not a specific stereotype or phrase, but more so just being aware of how stereotypes can influence your thinking about other people and how far off-base they actually can be.”

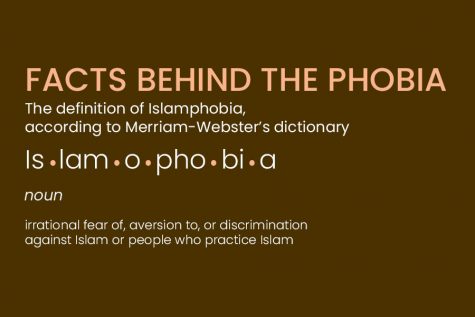

These kinds of stereotypes have become embedded and subsequently created a ground for psychological and structural violence against minority groups. Communications teacher Sohail Jouya – who is of Persian and Kurtish ancestry – comments that his skin color places him in a group strongly tied to racial stereotypes.

“Islamophobic racism has been a central component of life for most Muslims,” Jouya said. “Tropes of being violent, irrationally aggressive, and a threat is oftentimes coded onto people who look like me.”

Unfounded and irrational stereotypes are exacerbated even within school; freshman Gabby Delpleash has witnessed school faculty make comments that perpetuate inaccurate assumptions.

“Today specifically, one of my teachers insinuated that black people couldn’t swim,” Delpleash said.

Other teachers seek progress toward racial acceptance. Brignoni uses her class as an opportunity to open the floor to discuss these kinds of stereotypes. She’s come to the conclusion, after years of teaching, that people’s natural tendencies to judge often evolves into the harmful negativity that feeds malicious behaviour.

“It’s a natural inclination for us to want to categorize people, but unfortunately stereotypes have gotten so out of hand that most of them have become negative,” Brignoni said. “And we talked about it in class quite a bit. They started to try and come up with stereotypes that they’ve heard, and none of them were really very nice.”

Jouya, on the other hand, believes that mere discussion about stereotypes won’t produce any solutions for resolving these issues, but rather that an in-depth anti-racist training and curriculum is necessary for improvement.

“I’m actually not always sold that discussion of stereotypes themselves are particularly fruitful enterprises,” Jouya said. “I do believe that serious anti-racist training for employees and students would be a great idea and is long overdue.”

An awareness of racist behavior that would be brought about through such training would actually be able to resolve many instances of racism that happen in the educational sphere, according to Jouya. It would allow for those issues to be stopped before they become more of a problem.

“We’ve seen countless stories of white undergrads getting kicked off campus for using racial slurs, wearing blackface, and a number of other racist gestures,” Jouya said. “I can’t help but think that a number of those incidents could have been preemptively diffused by even the slightest of racial awareness training in K-12 education.”

However, stereotypes don’t always result in hateful comments. Junior Manoj Turaga and his friends commonly joke about being him being a “tech savvy Indian” – a stereotype often associated with his race, but one that accurately describes his own talents. Under these circumstances, he doesn’t see the harm in joking about it.

“I don’t think it’s bad; I like to take a joke. And certainly, I’m a different kind of person than most people in the world – I don’t get offended by things at all,” Turaga said. “Certainly, the things that people say to me, some people will get offended [from]. And I’m not the person to judge whether it’s racism or this stuff is okay; that’s up the person [the comments are directed at].”

Turaga notes that these comments sit differently when they come from strangers, though he recognizes that people don’t always have harmful intentions when joking about stereotypes.

“It is kind of weird, but they usually mean no harm. I don’t mean any harm whenever I do things [like that], and I hope that’s the case with them too,” Turaga said.

Brignoni describes how they can be a reflection of ignorance about a race’s history and culture.

“I think some people don’t realize what some stereotypes are based on,” Brignoni said. “They may go back to a time of war or time of oppression for certain people. Also, I think just people [say things] they’ve heard and they don’t realize the effect that it has on people.”

For instance, she has seen stereotypes represent misinformation.

“I’m surprised [by] how many people don’t realize that Puerto Rico is a Commonwealth of the United States, meaning that I am a born citizen,” Brignoni said. “Whereas some people will sometimes be like, ‘Do you have a green card to be in America?’ and I’m like ‘No.’”

Many minorities like Turaga exchange joking stereotypes as lighthearted fun, and others like Brignoni opt not to use them at all.

“You can make a heck of a lot of funny jokes without stereotyping somebody or at the expense of someone else’s culture,” Brignoni said.

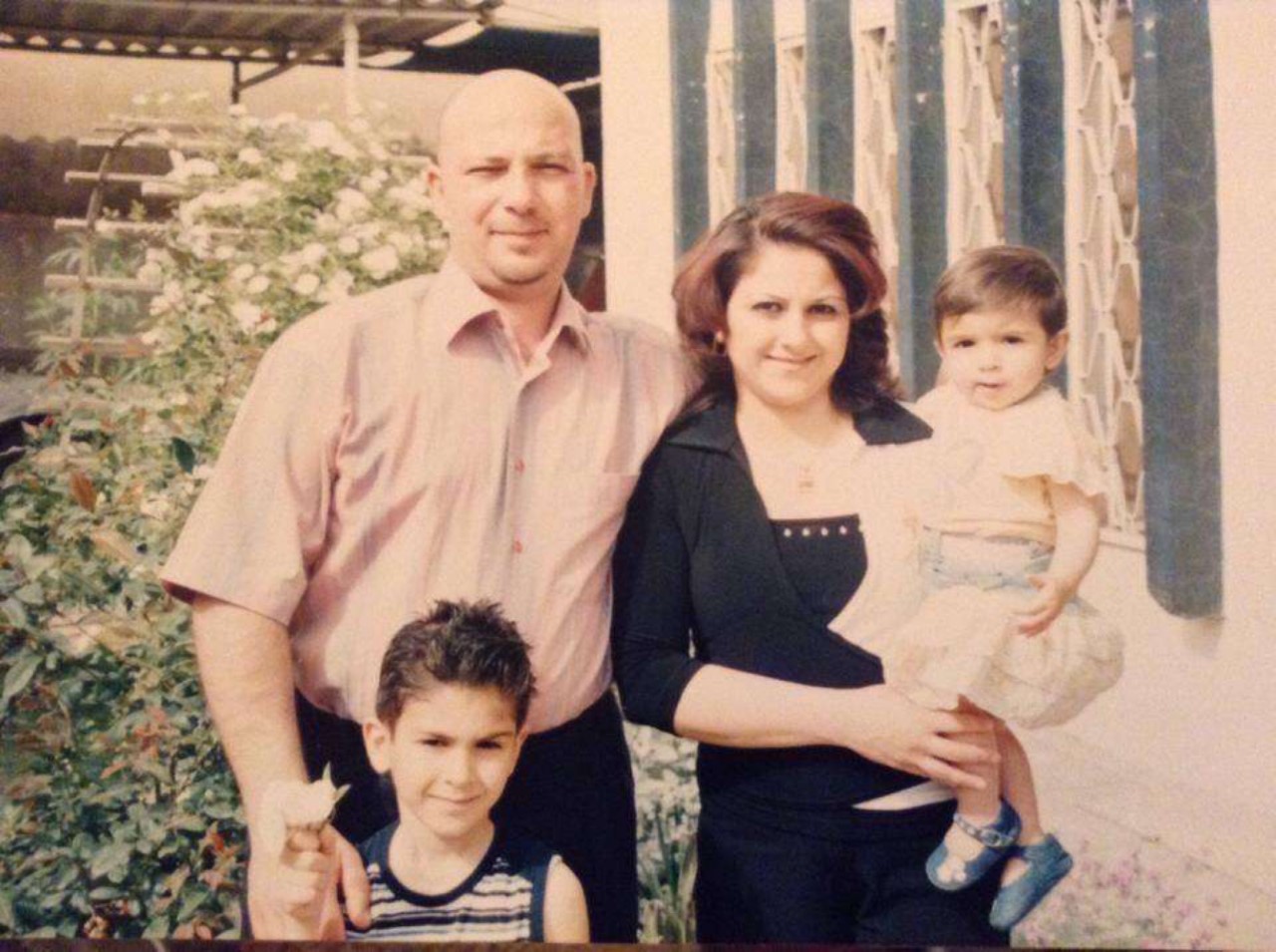

By Julia Fair // photo submitted by Deema Rashid

At three years old, sophomore Deema Rashid moved from Iraq to the United States. She has grown up in Kansas and has moved around a lot, but her culture is very present in her life.

Sophomore experiences discrimination founded in her Muslim heritage

Sophomore Deema Rashid moved to the U.S. at three years old and has experienced Islamophobia since then

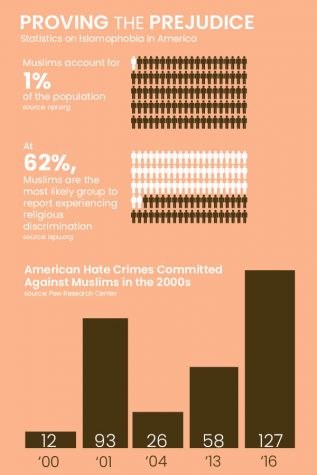

When sophomore Deema Rashid moved to America from Iraq, she felt alienated and left out by an imaginary idea, something that separated her from everyone else. She felt isolated and alone because she was different, because she wasn’t from the U.S. and because she didn’t look like everyone else. This racial prejudice has become increasingly common in society today and has opened the gate for Muslims to be portrayed as dangerous and ‘terrorists’ by the media.

Islamophobia can manifest itself in many forms: be it blatant discrimination and hatred or jokes made without a second thought. Rashid was born in Iraq and feels that her race has been consistently leveraged against her in jokes and comments. These jokes, according to Rashid, always become more common after something happens in the news that can be tied back to her race.

On Jan. 3, Iranian revolutionary leader Qasem Soleimani was assassinated by a U.S. airstrike, which directly led to fostering Islamophobia in America and increased the jokes and comments that Rashid gets.

“Ever since [the killing of Soleimani], I have been getting a lot of jokes,” Rashid said. “They get annoying after a while because they just aren’t necessary. When things occur and I come to school people mention it. When it gets overdone, it gets really annoying and sometimes some jokes cross the line and become offensive.”

This experience isn’t anything new either; Rashid feels that this discrimination has been directed at her since she moved to Johnson County in eighth grade.

“I moved to Monticello Trails in eighth grade, and I didn’t really feel like I fit in,” Rashid said. “Everyone would give me weird looks. They were welcoming but the hesitation and tension were still there.”

The feeling of doubt seemed to hover around Rashid when she first moved and the realization that it was over something she couldn’t change came as a shock.

“At first I didn’t really know why it was targeted at me and then I realized it was because of my race and I couldn’t really tell what to do about it,” Rashid said. “After time it passed by and became less common … but I’ve seen a lot more of it recently.”

University of Kansas law professor Raj Bhala is a prominent figure in the fight against Islamophobia. Bhala’s textbooks, essays, and publications speak out about the way that stereotypes manifest into hatred. As these stereotypes plant fear and insecurity in our minds, we begin to lose any empathy for an entire denomination of people; in society’s eyes, they have become a plague to be cured of and a threat to be rid of. This, according to Bhala in an email, is how Islamophobia becomes real.

“Islamophobia is borne of a lack of empathy,” Bhala said. “A lack of empathy is caused by a lack of understanding, which, in turn, leads to prejudice.”

Shari’a law is a form of religious Islamic law in which a lot of Islamophobia is directed at. State legislatures, including Kansas, have enacted anti-Shari’a laws to target Islam and perpetuate Islamophobia.

Bhala, a reputable source in Islamic law and culture, pursues a questioning of the implementations of anti-Shari’a law across the country and has spoken out against those laws on numerous media outlets and journals. He believes that the ubiquity of Islamophobia can be attributed, in part, to this anti-Shari’a legislation.

“Islamophobia has become more prevalent in recent years,” Bhala said. “Especially with anti-Shari’a legislation enacted by various states, including Kansas.”

According to Bhala, the proliferation of anti-Shari’a laws in Kansas in recent years is founded in ignorance of the debt that is owed to those who have been subject to discrimination in the past.

According to Bhala, the proliferation of anti-Shari’a laws in Kansas in recent years is founded in ignorance of the debt that is owed to those who have been subject to discrimination in the past.

“These bills are based on ignorance,” Bhala said in a 2011 interview with columnist Bill Tammeus. “The American legal system — many specific concepts in it — owes a debt, either direct or indirect, to the Shari’a. We have imported some concepts or some debates into our legal system that also are found in the Shari’a, and the Shari’a long predates English law from which our system more directly comes.”

Bhala compares this analysis to what it would be like to disown the kinship of your ancestors and trying to disassociate from your race and religion; it would be disingenuous.

“So it’s like banishing the blood of your great-great-great-great-great-grandparents from your veins. You can’t do it,” Bhala said. “It’s intellectually ignorant and disingenuous to do that … it’s absolutely thoughtless [to adopt such laws].”

To Bhala, the most effective way to combat this discrimination and build empathy is to stay educated on social issues and befriend people without worrying about race or religion.

“Comprehensive education about comparative religions, comparative constitutional law, and comparative legal systems are some of the ways, as well as people-to-people exchanges, to build empathy,” Bhala said. “Also, as a sports fan, I think athletic events are a healthy way to bring people of different faiths and countries together.”

Rashid believes that this feeling of resentment and hatred is often fostered from stereotypes that people hear and learn from others and that the only way that they know how to express that feeling is through jokes.

“A lot of the time people are worried about stereotypes and don’t know how to take that out except using words,” Rashid said.

When people don’t know how to take out feelings of distrust, the immediate reaction is lashing out with words, slurs and jokes.

Life at Home: Families share how their culture influences their lives

A look into how students’ diverse cultural backgrounds affect their day-to-day life

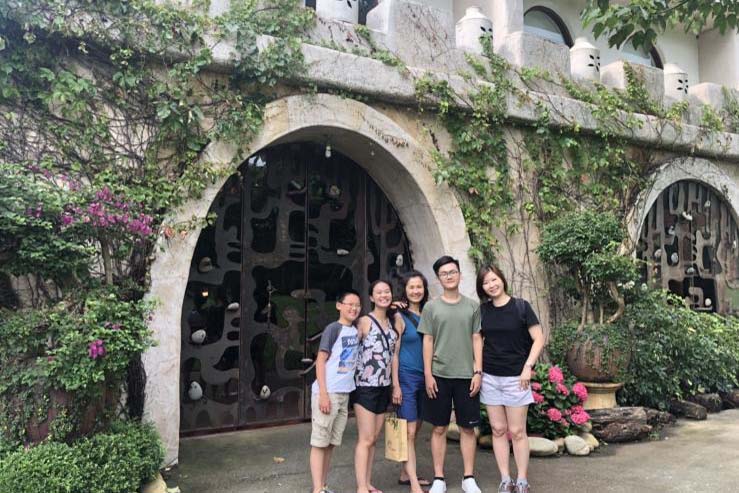

By Sophia Chang // submitted photo

Alongside her family, freshman Sophia Chang went on a vacation to Taiwan.

The Changs

Freshman Sophia Chang and her family value authentic food

Growing up as a first-generation US citizen has opened freshman Sophia Chang to two different cultures. Her parents had immigrated from Kaohsiung, Taiwan and with them, they brought the Taiwan culture into their through food.

Inspired by the food in Taiwan, Sophia’s father Scott Chang opened the restaurant Blue Koi to serve traditional Taiwanese dishes.

“It really was a dream of our family to own a business,” Scott said. “We grew up loving the food in Taiwan.”

Of all restaurant chains dedicated to serving Americanized Chinese food, Chang believes that traditional Asian food is a significant part of her culture.

“I just like eating Asian food; that’s like the biggest thing for me,” Sophia said.

With food being an important component of her culture, traveling to Taiwan has allowed Sophia to taste on the unique streets foods found only in Taiwan and connect with her extended family.

“We always visit mom’s family, and we usually take two weeks to do that,” Sophia said. “They take us everywhere to go eat a lot of food. We also take lots of pictures and road trips.”

While in Taiwan, freshman Sophia Chang visited the Miaoli Garden.

For Scott, being able to take his children to his native hometown of Taiwan is a worthwhile experience.

“It’s kind of like your parents homeland, so it’s almost how I feel like you are coming home,” Scott said. “People in Taiwan are just so friendly and welcoming.”

While Sophia is not able to speak Mandarin well with her family in Taiwan, she is able to comprehend what they are saying by listening.

“Although I can’t communicate very fluently with them, I still understand things that they’re saying because I’m more of a listener,” Sophia said.

While traveling to her parent’s home town allows her to connect with her culture, Sophia also has outlets to connect with her Asian culture in the community.

When she was a child, Sophia attended Chinese school where her mom was an instructor and her dad was part of the administration. Even though she no longer attends Chinese school, Sophia feels that the community there provided her meaningful connection with others similar to her.

“I think that the connection, the relationship with other like-minded Chinese is the most valuable,” Sophia said.

Despite being able to see an ample number of different ethnicities at school, Sophia believes that the school is accepting of her race.

“I don’t feel very anxious about going to school when I don’t see a lot of representative ethnicities at school because most people are pretty open-minded about it,” Sophia said.

By Courtney Mahugu // submitted photo

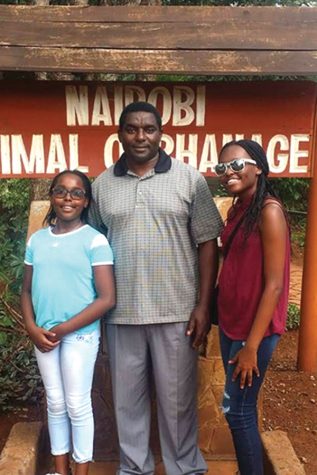

Over the summer, junior Courtney Mahugu took a trip to Kenya with her family

The Mahugus

Junior Courtney Mahugu’s parents are from Kenya

High school in America is a one of a kind experience. Experiencing it for herself and for her parents is something junior Courtney Mahugu has been doing for the past three years. Mahugu’s parents both immigrated to America from small villages in Kenya and are learning about American culture through Mahugu as well as keeping their own African culture alive.

With her family, junior Courtney Mahugu visited the Nairobi Animal Orphanage during her trip to Kenya.

“My parents went to highschool in Kenya… they really don’t understand what it’s like to be an American Teenager… so life is challenging a little because I have to explain a lot of things,” Mahugu said.

Mahugu’s dad, Francis Nuthu, tries to keep his African culture alive in his house through one of his favorite things: food.

“I try to maintain the African culture through food, music and language…” Nuthu said. “African cuisine is diverse and delicious.”

According to Mahugu, the authentic dishes that her mother makes at home requires spices that are not commonly found in the U.S.

“We cook only Kenyan food in my house…so there’s a lot of spices involved,” Mahugu said. “Although you can buy those spices in America, there’s a lot of spices…that are easier to get in Kenya.”

In addition to the food of her culture, the Mahugus connect with people that share their African culture through their church, Prince of Peace, once a month.

“It’s a Mass where there’s a lot of singing and there’s African garments everywhere,” Mahugu said. “Everyone’s wearing whatever country they’re from and singing songs from their country. I get to hang out with kids who understand what it’s to be Kenyan.”

Mahugu enjoys attending church because of the variety of style.

“Everyone’s hair looks different…everybody’s got a style going on,” Mahugu said.

By Amit Kaushal // submitted photo

For his first birthday, freshman Amit Kaushal visited his family in Punjab, India

The Kaushals

Freshman Amit Kaushal’s family blends American and Indian cultures

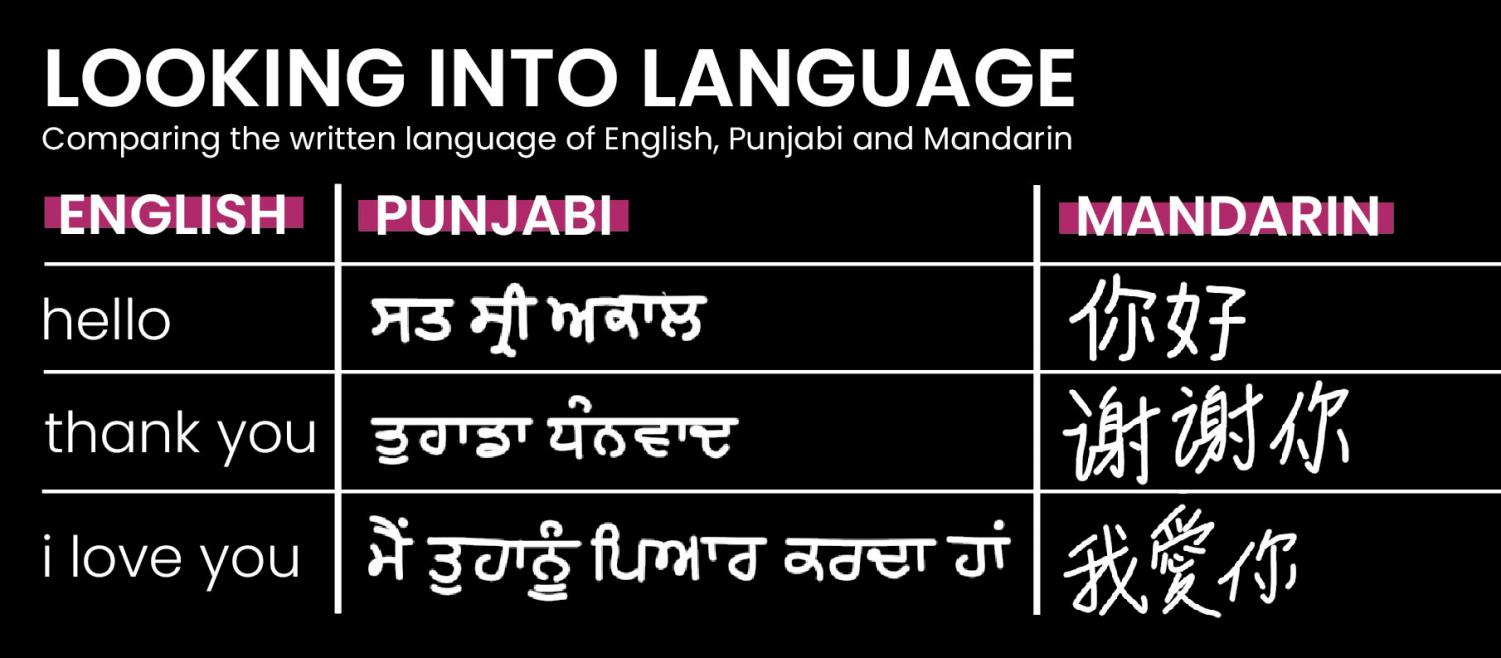

Growing up speaking three languages has always been normal to freshman Amit Kaushal. Kaushal speaks Punjabi and Hindi with his family, and English with most everyone else. Both of Kaushal’s parents immigrated to America from Punjab, India, and with them, they brought their language and culture. Kaushal’s mother, Kirana, followed her husband to America seeking a better life and a place to start their family.

“We came to America for a better life. My husband lived here, so I came here with him because I didn’t want to be by myself, and after we moved we didn’t want to go back,” Kirana said.

The Kaushals have traveled to India multiple times since immigrating to the United States, and while Kaushal believes he is too “Americanized” to live in India, he loves being immersed in the culture and being able to experience the unique differences between his two homes.

“There’s less technology in India, and in America it’s more advanced. In India, you can go on the roofs of the houses, and fly kites and here you obviously can’t. I think they’re both unique in their own ways,” Kaushal said.

The differences between American and Indian cultures have also been applied to Kaushal’s life in other ways, like his friendships. Kaushal feels more connected to the friends in his community because of the culture they share.

“I feel like with the friends in that community I can relate to them more since we have the same background,” Kaushal said. “We can crack jokes here and there about our culture.”

Kaushal notices that when he comes to school there are not many other people that share his ethnic background, which he says can be a good thing because it makes him more unique, but also limits him to be able to connect with people like him.

“Sometimes it has its perks of those like, ‘Oh, I’m the only one.’ It’s kind of cool, but then sometimes I wish there were some more people like me to connect with,” Kaushal said.

The temple the Kaushal’s attended is one place where Kaushal feels really connected with his culture. There is where they celebrate many Hindu holidays, including the most significant, Diwali.

“Our most important holiday is Diwali, the festival of lights,” Kaushal said. “It signifies good always wins against evil. We go to our temple and we light candles representing light and goodness.”

The Kaushals also celebrate American and Christian holidays, like Thanksgiving and Christmas, but for family purposes rather than religious reasons. Kirana’s reason for this was simple.

“We celebrate both and there’s nothing wrong with that because we are living here, and now we’re mostly American,” Kirana said.

Kaushal believes that attending services at his temple, his mother’s cooking, and speaking Hindi and Punjabi has helped him embraces and keep his culture alive, which he hopes to continue to do.

“I want to pass it down to my kids and I want my kids to pass down to their kids because I want to keep it going,” Kaushal said. “My parents immigrated here and they kept it alive. That’s what I want to do too because it’s my roots.”

By Ashleen Toor // submitted photo

Along with her brother, junior Ashleen Toor visited Punjab, India when she was three years old.

The Toors

Speaking Punjabi at home is an important part of junior Ashleen Toor’s culture

The first words she said as a child weren’t in English; it was in Punjabi. Her parents immigrated to the U.S. to provide her and her siblings with more opportunities. While her parents left their native country, they made sure to pass on the Indian culture to their children. Even as a first generation U.S. citizen in her family, junior Ashleen Toor’s life at home closely resembles her parents’ native Indian culture.

Growing up, Punjabi has been Toor’s primary language. While she speaks English at school, at home and at her temple, Toor primarily speaks the native language that her parents had taught her first. Being able to speak Punjabi has opened doors for Toor to communicate in her native language when she travels back to India.

“I can communicate with people from my culture and people who I live with,” Toor said. “I feel like it’s a good thing to know because whenever we visit India, it’s really helpful to know what other people are saying to you and how to communicate with people.”

In a wadding tradition, junior Ashleen Toor makes a rangoli.

In addition to teaching her children how to speak Punjabi, Toor’s mother Kirendeep Kaur has taught her children about their culture and traditions in order to maintain their native culture.

“We try to speak our language and tell our kids what our culture and traditions are,” Kaur said.

Beyond her life at home, Kaur also takes Toor and her siblings to their temple, the Midwest Sikh Gurdwara, to immerse her children into a community that shares a commonality of the Indian culture.

“We have many programs in our church, so we try to take our kids over the years so they can know what Indian culture actually is,” Kaur said.

According to Toor, over 400 families at her temple share a close relationship on the basis of their religion and language.

“We’re really close knit, everyone knows who everyone is,” Toor said. “We all just come together on the basis that we’re all Sikh, and we all speak Punjabi, and that’s what we all relate to.”

While the community at her temple and her family has allowed Toor to connect with people of her culture, traveling to India has allowed Toor to truly appreciate her Indian culture.

“I love it. When we go there, I just love seeing the culture, the food, all the people talking, the clothing, everything makes me feel really proud of my heritage,” Toor said.

Despite not being able to see many students that share her culture at school, Toor is glad that her peers are open to learning about her Indian culture.

“I like that people are able to accept me for who I am; people actually have an interest in my culture,” Toor said. “It makes me happy to know that people you know want to learn about your culture.”

By John Sleezer/Kansas City Star/TNS

Sharice Davids gives her victory speech after winning the state’s 3rd congressional district race on Tuesday, Nov. 6, 2018.

Representation in Politics

Despite recent strides, minority students and teachers feel underrepresented in politics

Imagine looking up at your community leaders, at your representatives or even looking at the president and seeing someone who doesn’t look like you. Think of how discouraging that would be, and how your entire life you would see politics dominated by people who don’t look like you, don’t talk like you, don’t think like you and don’t have the same priorities as you. That is what people of color face every day.

History teacher Aaron Cox sees the fact that elected officials in the U.S. do not represent the country’s demographics to be a major problem.

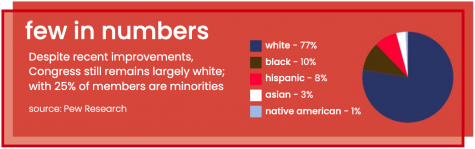

“When you look at politics … and at our demographics, there’s a lot of categories that are underrepresented,” Cox said. “It’s no secret that most politicians are white, and they’re male. I don’t think it’s just African Americans that are underrepresented. I think women are underrepresented and I think there’s a lot of minorities that are underrepresented.”

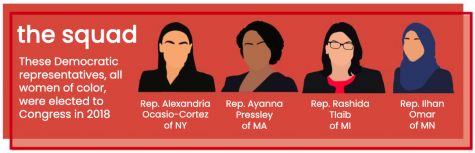

While, according to Vox, Congress is the most diverse it has ever been, it is only 22% non-white compared to 39% of the total population that is non-white. Although Kansas has also improved in terms of representation with the election of Sharice Davids, the other five congressional representatives are white, leaving the majority of the state without minority representation in congress.

In addition to Cox, junior Adam White feels that government organizations are not sufficiently representing people of color.

“I think from both a numerical standpoint as well as a power representation standpoint, neither metric is fulfilled by the amount of representation within government for underserved minority groups,” White said. “Congress and other governmental positions are dominated by white straight males and I think that is an issue, and it doesn’t represent a lot of the interests of minority groups.”

Senior Tripp Starr feels that the lack of diversity in the political realm discourages people of color from being involved in politics.

“It’s kind of disappointing,” Starr said. “You want to see people in the light that look like you, especially in the political realm because it has some deeper meaning.”

Throughout Cox’s life, politics has been dominated by predominantly white males.

“I’ve kind of grown up in a society where that’s the case,” Cox said. “I think that it’s kind of the norm unfortunately, and so I’m used to it, but I’d like to see that change.”

While not perfect, Cox feels that Congress and other government organizations are becoming more inclusive.

“When we look at the demographics there’s more diversity,” Cox said. “Congress is more diverse now than it has ever been, so I think we’re trending in the right direction.”

While White concedes that representation in Congress has gotten better, he still feels there’s a lot that needs to be improved.

“Improved is a relative term,” White said. “Since, you know, our good old days in the late 1700s, when literally everybody was a white straight male, I think it’s fair to say that we’ve added in a couple of people of color to Congress, but we still have a lot of room to grow.”

This increased representation that Cox argues for is meant to increase minorities’ influence.

“They need [a] voice,” Cox said. “You’re not going to have a voice if you’re not represented in some way. We all want to be able to have an opinion, and we all want to be able to have a voice, and you have to have that representation with people that are similar to you.”

While Cox understands the importance of political representation now that he has grown up, he didn’t see it as important when he was a kid.

“To be honest, growing up, I think I was like a lot of students. I was in my own box, doing my own thing I didn’t understand the bigger picture,” Cox said. “Now that I’m older, being able to have a bigger picture outlook, I wish I would have paid attention a little bit more.”

For Starr, representation is improving but the fight for representation is still an important one.

“I feel like there could be more representation for people of color,” Starr said. “I feel like that society has improved in some ways, but there’s still more room for improvement.”

White feels the solution to problems of representation is clear: increase voting rights for all.

“I think cracking down on issues of gerrymandering as well as reducing voter restrictions [is important],” White said. “There have been voter restriction attempts in places like Georgia and other places that make it very difficult to go to the polls for people and oftentimes is clearly benefits the white people within America in their attempt to maintain control over the government.”

The solution to the problem for Cox is to get the younger generations involved through government or civics classes.

“I think we need more involvement,” Cox said. “We want a younger generation to get involved, and I think that starts with education … getting kids interested in politics and teaching them how to get involved … will start to increase the diversity of the people running for public policy.”

By Al Seib/TNS

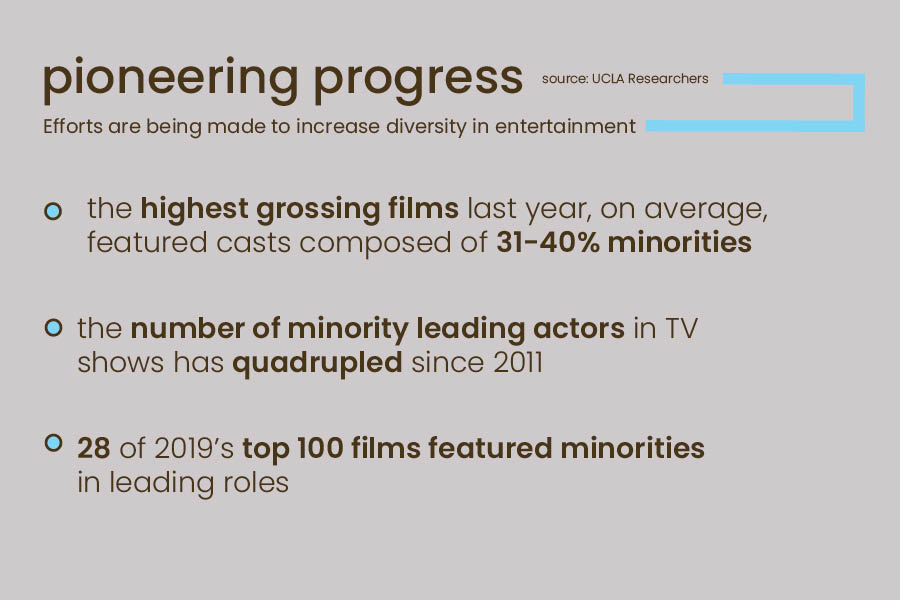

“Parasite” director Bong Joon Ho cheers his cast’s landmark win, marking the first time in history that a foreign-language film has won the SAG Award for best ensemble.

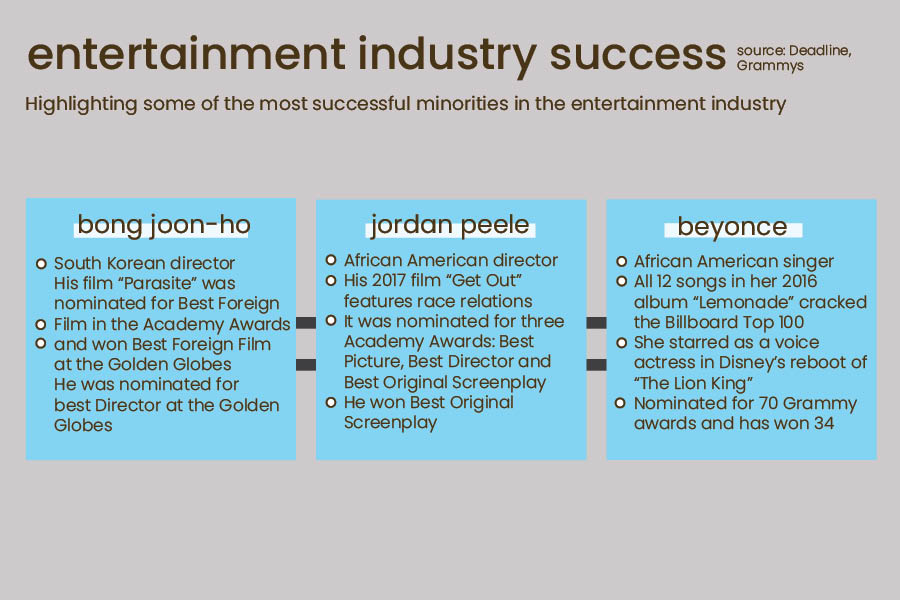

Representation in Entertainment

A graphical representation of the successes for minorities in entertainment and where there’s still room for progress

By Andrew Tow

Together, senior Nico Gatapia and his father Ramulus Gatapia make Kaldereta.

Senior cooks traditional ethnic family dishes

Senior Nico Gatapia makes traditional Filipino dishes with his family

Kaldereta, a traditional Filipino stew makes senior Nico Gatapia feel closer to his culture. Nico’s family uses recipes passed down through family members from the Philippines.

“I get to experience my family’s culture without visiting the Philippines. Food is the only thing that connects me with my family’s culture,” Gatapia said. “Filipino food offers variety and I feel bad for people who don’t have access to authentic ethnic cuisine.”

According to Nico’s father, Ramulus Gatapia, he started teaching Nico to cook se he would be able to take care of himself and connect to his Filipino history.

“We’ve been teaching Nico [to make Filipino food] since seventh grade, at the same time we started teaching his sister Camille, so that they develop cooking skills as well as be independent when they attend college,” Ramulus said. “It’s also to strengthen their sense of Filipino identity.”

Nico hopes to continue the tradition of making Filipino food with his kids.

“I’d like to continue cooking Filipino food in my future. If I have kids I’ll pass it down to them so they can experience the same culture,” Nico said.

Staff editorial: Continue to be accepting of different cultures

Being open to learning about people’s stories will help us accept different races

Racism is an issue that many think has been solved. Slavery, segregation and so many other racist policies have been abolished and programs like affirmative action are pushing us one step closer toward complete equality. Despite this seemingly growing acceptance of other races and cultures, America, including Mill Valley, still has work to do in regard to racial equality and that starts with being understanding of other cultures.

While no one is arguing that America is worse now than it was in the 1700s, recent white nationalist backlash has made America a less inclusive place. Although most people have no intent to mirror racist actions of the past, racism from positions of power spills down to everyone, including students at Mill Valley.

Whether it is the backlash from events such as 9/11 or the prevalence of racist memes on social media, teenagers are becoming increasingly exposed to racist opinions. Tweets from President Donald Trump telling four congresswomen of color to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came” lead many to have an unfair bias toward people of color.

These circumstances make it crucial that people think before they speak and are willing to change their behavior if it offends someone else. One way to increase awareness of these issues is to learn about the problems other races and cultures face and work toward understanding.

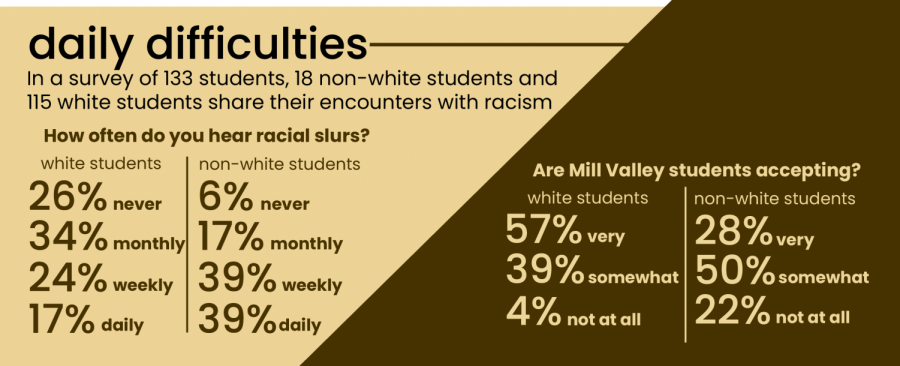

In a survey of 133 students, 57% of white students say that Mill Valley is very accepting of different cultures and 28% of non-white students agreed. While Mill Valley is generally accepting of other cultures, accepting is completely different from understanding. By understanding someone else’s culture, you understand why they are who they are, how they learned what they learned and better understand who they want to be. This can be accomplished by listening to others stories and by resisting the urge to support racist posts on social media. While we can not change the racial diversity at our school, taking the time to learn about different cultures will not only allow us to be more understanding, but it will also broaden our views of the diversity all around us.

Whether it is race, culture, disability, gender, religion or anything else that makes people different, understanding the history and importance of their beliefs not only helps you to better connect with them, but also to reduce racism whether it be in person or online.

Sofia Tollefson • Feb 21, 2020 at 12:27 pm

This is amazing! The entire page is so cool! The visuals are great and so is the content!! I’m super impressed, keep up the great work!