Expectations of privacy differ among students

Due to a recent privacy breach, laws and policies regarding privacy are reviewed

September 28, 2016

A recent criminal investigation involving a male student taking inappropriate and illegal photos of female students while at school has raised questions about student privacy in the digital age.

The male student, who no longer attends the school, was reported in May 2016 after taking several inappropriate photos and videos of female students from Friday, Feb. 5 through Monday, May 2. The photos were taken in the school, during the school day.

The male student took pictures of private areas, which, according to Kansas law, indicates a violation of privacy, even though the pictures were taken in a public place. This violated Kansas Statute 21-6101 subsection six, which states that using a camera to take photos or videos of others with an intent to view the body or undergarments without consent is illegal, and classified as a level eight person felony.

A senior girl, who wishes to remain anonymous because she doesn’t want to be associated with the case, said she saw the male student “holding his phone up under a girl’s skirt … walking up the stairs.”

The student was charged with 11 counts of breach of privacy and was charged with juvenile diversion. According to the Johnson County District Court, juvenile diversion is “a program for juveniles with no prior offenses who commit less serious offenses and are therefore given a “second chance.”

Student resource officer Mo Loridon declined to comment regarding specifics of the case.

The issue of privacy is not confined to only this case; privacy is an open-ended subject that pertains to several people and aspects of technology.

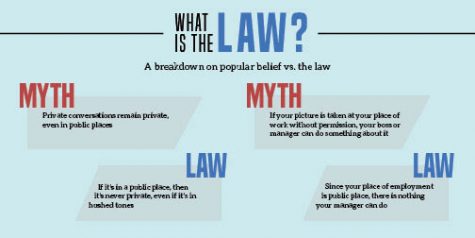

According to state law, a “private place” refers to “a place where one may reasonably expect to be safe from uninvited intrusion or surveillance.”

The violations of privacy range across a broad spectrum, from personal privacy to technological privacy, according to Loridon.

“[Privacy is] a broad term. Everybody looks at privacy a little bit different,” Loridon said. “Privacy can be space, like if you’re too close to someone. Privacy can be touching someone when they don’t want to be touched. Privacy can mean lots of different things, like listening into conversations.”

Loridon said that legal lines are sometimes blurred because privacy depends on a specific person’s expectation and definition of privacy, which may differ among victims and situations.

“You have to have an expectation of privacy with your own [personal values],” Loridon said. “You shouldn’t have an expectation of privacy in C-hall, for example, there’s other people in there. But, you should expect privacy in bathrooms or other places you would expect to have privacy.”

Sophomore Lauren Rothgeb said that she isn’t knowledgeable regarding Kansas privacy laws, but thinks she and high school students should be.

“I wouldn’t say I know that much [about privacy laws],” Rothgeb said. “I should know more, but I haven’t put that much thought into it before.”

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center showed that 92 percent of American teens report using the internet at least once daily, while 71 percent use at least two social media networks.

According to junior Lilly Blecha, privacy should be expected on the internet when someone indicates that they want privacy, such as in instances where people make social media profiles private.

“The internet isn’t a very private place in general so if I’m going to post something online then I have to expect that it’s going to be out there [for everyone to see],” Blecha said. “I like to control who can see my [personal posts].”

While there is an expectation of privacy in the instance of social media, it isn’t always met by everyone, as was the case of an anonymous junior girl.

The girl student consciously sent a partially-nude photo of herself to another male student over Snapchat, intending for the picture to disappear after three seconds. Instead, however, the male student screenshotted the photo.

“I expected [privacy] because I trust the person I sent [the picture] to,” she said. “I think that any time, at least in my instance, that you send [an inappropriate] picture then you expect privacy because if you were meaning for it to be for more than one person, you would send it to more than one person.”

The anonymous junior girl said if the male student shared the photo, she believes her privacy would be violated.

“I would be petrified [if anyone found out], because it’s not something I’m proud of, and I wish I’d never done it,” she said. “If someone found out that about me I wouldn’t want that to shape the way they think about me.”

If the male student shared the photo, he would be violating subsection two of Kansas Statute 21-6101. This section states that divulging the contents of an inappropriate message without the consent of the sender is illegal, and classified as a Class A nonperson misdemeanor.

According to Loridon, teens should be aware of posts to social media networks because of “future implications” of questionable posts.

“If you’re a senior and you’re saying stupid things on social media, then your colleges will see that,” Loridon said. “Colleges and jobs check social media. That’s a big thing for me — not just invading privacy, but also putting your privacy out there for everybody to see.”

This issue of privacy impacts a wider range of students further than Mill Valley, according to Loridon.

“This is a problem with every single school,” Loridon said. “They have problems with this in middle school. Now they’re having problems with this in elementary schools, because people are giving their kids phones in second or third grade who are on social media. It’s not just at Mill Valley; I have friends who are SROs at other schools and they have the same problems we do.”

If one witnesses or is victim to a breach of privacy, contact Loridon.

Ultimately, Blecha said that students should be informed of laws and policies relating to privacy.

“Everybody should have awareness on privacy and how to make things private when they want it to be,” Blecha said. “We’re just a bunch of high school kids, and we’re kind of dumb with our social media, so we should know privacy and understand it.”