Integration of STEM in education encourages students to explore interests and future careers

An analysis of district curriculum, college readiness and job market options

February 17, 2018

Though the current discussion about what K-12 curriculum should look like is often dividing and polarizing, there is one common ideal most Americans can agree on: high school students need to be more prepared for careers in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). The push toward STEM is seen at both the state and local levels, from curriculum reform in Topeka to the integration of technology in the classrooms of Mill Valley. According to the Pew Research Center, 34 percent of Americans would tell a current high school student to pursue a career in STEM. Additionally, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts employment in STEM occupations will grow to more than 9 million between 2012 and 2022.

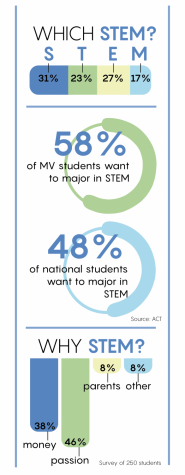

This emphasis on STEM can be seen not only in our halls, but throughout the district and throughout the country. And though as students we seem to hear about it constantly, the actual implementation of this STEM curriculum is somewhat complicated and misunderstood. With almost half of the 1.9 million seniors who took the ACT in 2015 entering a field in STEM, it is necessary for them to understand the field they are about to enter.

District-wide

District offers multiple pathways to pursue STEM from elementary through high school

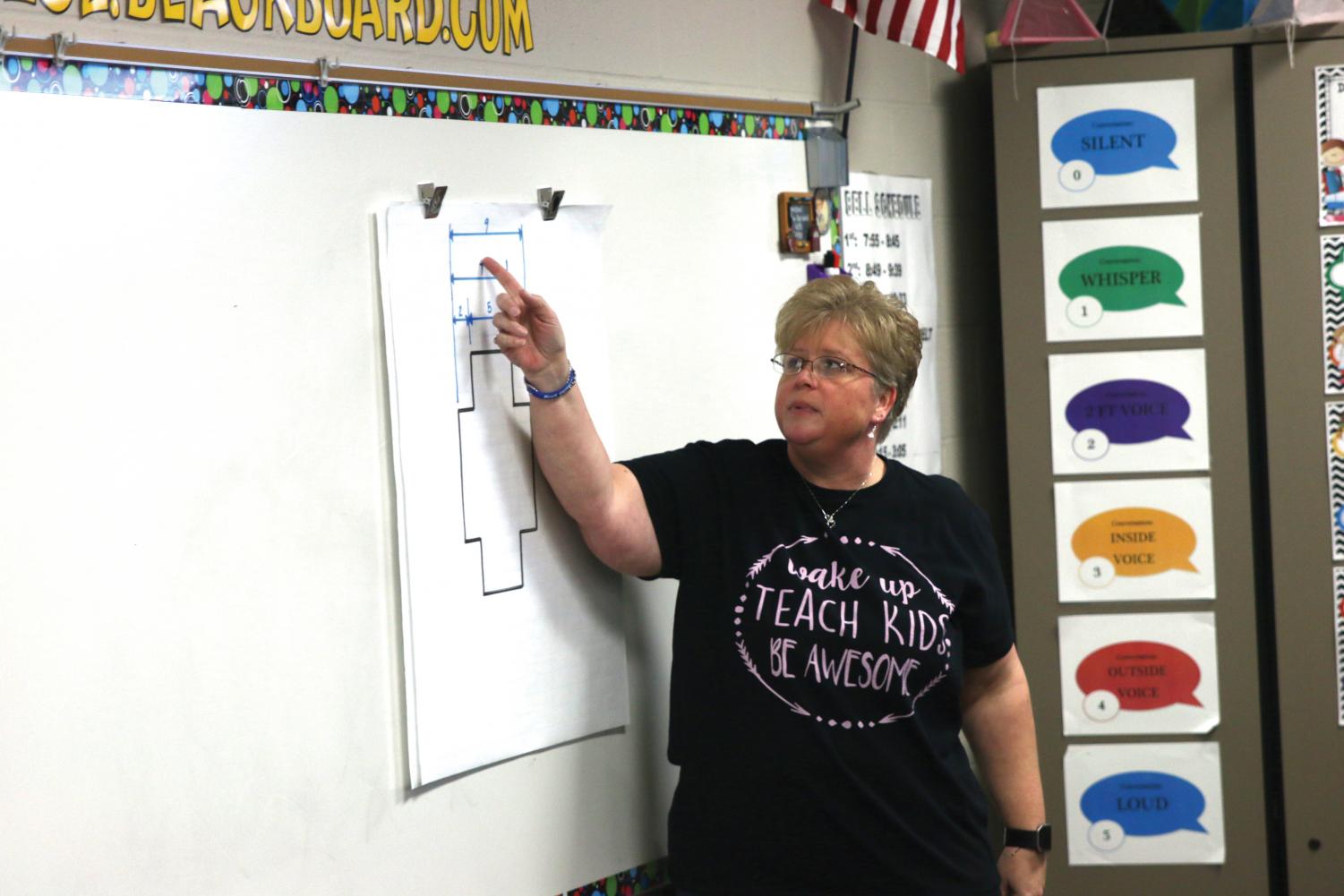

If there is one word to describe the climate of Mill Creek Middle School engineering/technology classroom, it would be “crazy.” Engineering teacher Denise Legore-Seawood uses the word herself, and on the afternoon of Friday, Jan. 19, that description is fitting. There are 32 eighth grade students, 11 of which are girls, beginning a project focused on architecture and drafting. Throughout the room are positive affirmations encouraging confidence, and Legore-Seawood wears a t-shirt with a simple mantra: “Wake up, teach kids, be awesome.”

On the board is a large piece of graph paper with a shape and dimensions on it, and Legore-Seawood is directing her students the correct way to copy the drawing. One student from the center table asks about the arrows on the end of the dimension lines, creating a loud discussion between the students which ends in applause as they find the answer. By the time the bell rings for the end of the 45-minute class, one boy pleads “Please let me stay.”

Legore-Seawood’s classes are in the middle between the basic computer classes of the elementary schools and the engineering pathways of the high schools. Her classes range from the principles of flight and aviation to bioremediation. Her eighth grade classes, however, study architecture and engineering concepts in order to provide a foundation for high school curriculum. Despite the hyper-energetic atmosphere of the room and the loud chatter of students, Legore-Seawood loves her job.

“Why would you not teach this class?” Legore-Seawood said. “I get to play with airplanes. I get to build rockets. I get to cut things on power tools. I get to draw on paper … I have the greatest job ever.”

Between drafting on computers to graphing measurements, Legore-Seawood’s class is the epitome of STEM curriculum, yet she emphasizes the importance of the soft skills her class utilizes.

“This is about lighting the fire,” Legore-Seawood said. “It’s community building, it’s how you work together in a cooperative group, it’s communication, it’s team-building, it’s sharing, it’s problem solving, it’s being creative, [and] it’s ways to do those things.”

During seventh hour on Friday, Jan. 19, Mill Creek Engineering teacher Denise Legore-Seawood explains the importance of drafting.

This goes hand-in-hand with the technology standards implemented by the district. According to district Career and Technical Education Coordinator Cindy Swartz, technology education “can assist with student engagement, creativity, critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and innovation.”

Legore-Seawood’s class has been continually adjusting to coordinate with the engineering and technology curriculum taught at the high school level.

“Everything is changing because the state is changing, so we’re looking at individual pathways,” Legore-Seawood said. “The dream scenario is that if you knew what you wanted to be, you’d be taking classes in high school to get you towards that path.”

That path can vary between high schools, though. While some STEM courses are only offered at certain schools, such as Zoology here and AP Computer Science at DHS, the district’s goal is “to use our resources efficiently to ensure that students have great learning opportunities, regardless of which school they attend,” according to district Director of Teaching and Learning Joe Kelly.

“In the state of Kansas, there is a new movement to include Individual Plans of Study (IPS), which helps students make decisions about their education based on career interests and goals,” Kelly said. “Staff members are continuing to look at ways in which we can identify a student’s interest in STEM fields and encourage the exploration of STEM possibilities through the Individual Plan of Study.”

STEM education is also integrated into the elementary schools. According to Horizon Elementary technology teacher Sarah Midiros, students focus on “basic computer skills such as typing, learning how to use a Word document, and creating PowerPoint presentations,” alongside skills such as coding, 3D printing, and video game design.

“If you think about it, STEM is invading our students’ world as they know it,” Midiros said. “It is imperative we effectively teach students critical thinking skills as well as let them create, have the opportunity to fail and troubleshoot to achieve an end goal.”

Even teachers here are incorporating new district standards into their classes. Technology teacher Helga Brown said that over the last few years, the district has shifted their focus from simply learning engineering concepts to more engaging curriculum that will effectively help students more later in life.

“The district is embracing the whole Common Core for more applied math, applied science, applied technology, so not like learning keyboarding for the sake of learning keyboarding, but learning how to use the computer as a tool,” Brown said.

During Engineering Design & Development on Thursday Jan. 25, senior Maggie Miller works on a prototype for her belt clip.

Brown explains how the state’s changing standards for her classes have shifted to a computer-based curriculum, specifically in her Drafting/CAD class.

“Five years ago, when I was teaching drafting … we had to teach them how to letter. It’s a big deal, and we would spend two or three weeks on learning how to letter,” Brown said. “So we completely dropped lettering, which opened up the opportunity to get that 3D modeling in there. No longer were we teaching three weeks of lettering and spending half a year drawing on paper, we were doing quick, basic skills you need for sketching, then right into CAD.”

Brown said the evolution into a computer-based class is a positive change, especially the addition of the free drafting program Revit, and is excited to see where her classes will go in the future.

“I love that it’s evolving,” Brown said. “I love that like three years ago, we implemented Revit and I’ve been running with it since. And most of it is self taught, just jumping in and figuring out how to use it, and the kids like it.”

College

High school allows readiness for STEM studies in college

Due to the priority placed on STEM careers and the increased wages for occupations in the field, the number of students entering college with the intent to major in a STEM field has increased dramatically over the past years. According to a 2015 study conducted by the ACT, the number of high school seniors interested in STEM has increased from 780,541 in 2011 to 939,049 in 2015, with the percentage of students interested in computer science and math majors increasing by 2 percent. In order for all those students to be adequately prepared, teachers have stressed that practicing skills needed for STEM in high school is an important forerunner to succeeding in college.

Brown said she encourages her students to find part-time jobs that use Revit, the current standard modeling software used in architecture, to make “good money” instead of minimum wage. That way, students can put skills learned in high school into use.

“We’re building those skills, building industry standards so when they go to college they’ve got a leg up with other schools that aren’t using Revit, that aren’t using the software we’re using,” Brown said. “But colleges are, so they go and they already kind of know their way around.”

With the amount of academic scholarship opportunities available, as well as high starting wages, the appeal of going into STEM is lucrative, but students must be prepared for the rigor of “hard science” courses in college. Counselor Chris Wallace explains that although difficult math and science classes will prepare you for that pathway into your major, taking English, history and art is also recommended.

“Even though STEM is typically thought of as being strictly about science and mathematics, you still need a variety of educational backgrounds in order to be successful in those industries,” Wallace said. “Though taking classes like physics and higher math classes … are always a good idea, it’s still beneficial to also take your English classes and some of those [other] classes seriously.”

Pouring sand into a bucket, sophomore Eva Burke participates in the tower competition at the Northland Invitational on Saturday, Jan 27th. “I think a lot of girls don’t think of STEM as a job they can do.” said Burke.

Additionally, activities outside of school can prepare students for STEM careers in the real world. Extracurricular activities such as FIRST robotics, Science Olympiad, Skills USA or JagFlite can help students explore their interests and see if they would actually enjoy a career in STEM. Robotics president senior Amanda Hertel said robotics has allowed her to implement what she’s learned in the classroom into her extracurricular interests.

“[Robotics] really helps you to see a real world application,” Hertel said. “It’s not just book smarts. A lot of times with engineering and technology, you need the real world skills as well as the book smarts, and with robotics you’re able to apply the concepts you’re learning in class to whatever you’re working on in the robot.”

Similar to Hertel, junior Sydney Clarkin said her participation in Science Olympiad has allowed her to explore her interests, and expressed that clubs at school offer students a chance to relax while they still practice STEM concepts.

“In some ways, it creates a less structured environment where kids are still able to learn,” Clarkin said. “I’ve been inspired by it and I hope that whatever I do can help people.”

Hertel emphasizes that STEM is becoming the field of the future.

“It’s all about innovation and design,” Hertel said. “It’s where our world is headed. Robotics and things like that — that’s our future.”

Job Market

STEM continues to grow as a field and in pay

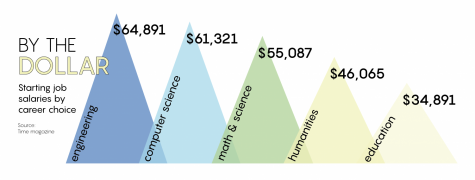

According to a survey of 263 students, 57.78 percent of students at the school are interested in pursuing a career in a STEM field, with 38 percent of those students motivated by the high wages STEM careers can give. And the wages can be lucrative. A report from the U.S. Department of Commerce notes that those working in STEM can earn 26 percent more income than those who are not in STEM.

Wallace notes the level of student interest in STEM has grown as the field has become more prominent.

“The typical benefit is that jobs are available; it’s not a shrinking market,” Wallace said. “It’s an expanding one, so it’s usually pretty easy to get a job coming out of school. You can usually make a good amount coming right out of school [where,] if you had to take on some student loan debt, you could manage that pretty well.”

The statistics agree. The STEM field has been growing over the past decade, with 17 percent growth projected from 2008 to 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. These numbers are drastically higher than the growth projected for other fields, which had a projected rate of 9.8 percent from 2008 to 2018.

“There’s all these problems, and STEM lets you solve those problems,” Gothard said. “It pushes society forward. It lets you get past your old problems so you can get to the new ones. It helps invigorate economies, it helps invigorate technologies and science and lets you go more in depth. It’s just a driving force that allows humanity to go forward.”

However, there has been a notable lack of diversity in regards to the makeup of STEM occupations. While women make up more than half of the workforce, according to a survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2011, only 26 percent of workers in STEM fields are female.

Even so, sophomore Eva Burke, who is interested in pursuing biology, believes that the STEM workforce will grow more diverse in the future.

“When you look around, there aren’t a whole lot of female scientists,” Burke said. “I think that’s going to change in coming years as society is progressing. It just takes a little bit for the workforce to catch up with that.”

And as STEM grows, Legore-Seawood sees the field becoming more accessible to students of all backgrounds and capabilities.

“STEM is not for geniuses,” Legore-Seawood said. “It’s not for the cream of the crop. It’s for everybody. And it’s finding your level of where it fits.”