The effects of stereotypes and racism are felt within the school and community

February 13, 2020

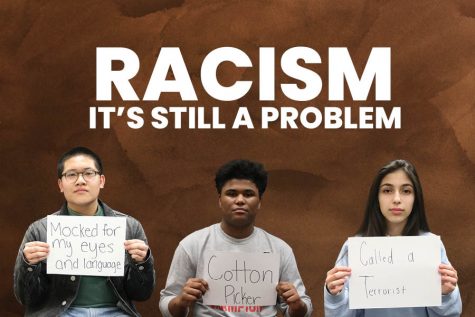

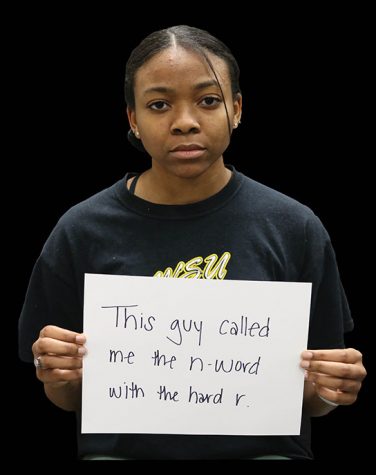

Participants were asked to recall a time they had experienced racism within the school or community.

Sophomore Drew Morgan shares his personal story

Morgan sheds light on how racism and stereotypes have impacted his life

An elderly, white man approached the baseball field concession stand. He stopped to stare at sophomore Drew Morgan who was busy preparing a large order of Icees. After finishing his task, Morgan greeted the man and apologized for the wait.

“You’re lucky your people are allowed to work here,” the man said.

Ignoring the comment, Morgan asked again how he could help the man.

“Back in my time, your people wouldn’t even be allowed to be in this certain section,” the man said.

Not wanting to lose his job, Morgan replied that he couldn’t help the man if that’s all he was going to say. Without another word, the man walked away.

This blatant racism was not the first time Morgan’s African American ancestry played a role in how people treat him. Adopted into a white family, the color of his skin began shaping his world before he even understood what race was.

“I remember when I was growing up … a lot of people would stop and stare at my family in public, and it was something that I didn’t understand at the time,” Morgan said. “[I thought], ‘Why are they staring at me?’ I was just staring at my parents.”

While Morgan recollects the discomfort that dominated these moments, he recognizes that it’s natural for people to do a double-take when they notice his family’s unique dynamic.

Exiting the gym floor, sophomores Drew Morgan and Caelia Hissong finish playing the game.

Race grew to be a larger aspect of his identity upon entering grade school and not always in a positive way; Morgan often felt disconnected from his white peers who didn’t share the same race-related experiences that had become increasingly prevalent.

He feels these problems have been partially alleviated since he started high school. The increased diversity allowed him to find students who are “really vocal about how they feel about being black, how they feel about how they’re treated.”

However, Morgan is no stranger to the notorious history class situation that countless black students experience throughout their education: the room full of non-black students that inevitably turn toward the single black student when it’s time to discuss the Civil War or the civil rights movement. While Morgan doesn’t blame others for this reaction, he sheds light on why this kind of occurrence creates an unpleasant environment.

“A lot of people will turn around and look at me or turn toward me,” Morgan said. “It’s extremely uncomfortable for me. It’s just a lot of eyes on you for something that you can’t really control.”

Morgan also hears malicious comments made at school based on racial stereotypes stereotypes tied to black people.

“There’s a good amount of people at Mill Valley who, whether it’s a joke or not, say ‘black community: there’s crime, criminals, a lot of just violence.’ I think that’s what a lot of people like to push as a stereotype that we’re a violent community of people,” Morgan said. “I’ve also seen some people say we’re ghetto, that we’re not educated well enough, [and] that we can’t speak proper English.”

A stereotype that Morgan is especially bothered by is that black people are inherently more violent than white people. Morgan thinks this ill-founded stereotype is exacerbated when people only look at shallow statistics and don’t address underlying causes behind those issues.

“[The stereotype] that all black people are ghetto… kind of irks me a little bit, because there are a lot of black people who don’t act ghetto. No one wants to act ghetto; it’s the situation that they’re in,” Morgan said. “A lot of people don’t grow up in great places … in order to cope with that, they get into violence. And it’s not the right thing to do, but it’s the only thing they know.”

While high school was a step up in terms of racial diversity within the student population, which allowed him to interact with peers who he can speak to about these problems, this doesn’t mean it’s always easy. Going to a school with a primarily white staff has limited the number of adults in Morgan’s life that are fully capable of understanding these race-related aspects of his life.

“It’s a little bit hard because when you’re trying to explain a situation that you’re going through, or something that’s happened to you in school, or maybe someone’s saying something,” Morgan said. “It’s hard for them to put themselves in your shoes, and vice versa.”

The impact of racial stereotypes

Students and teachers address the stereotypes tied to their appearance, culture or ethnicity

Racial stereotypes are often innacurate representations of individuals.

Since moving from Puerto Rico to the U.S. when she was four years old, English teacher Coral Brignoni has been unable to escape the stereotypes tied to her race. She may have been born a U.S. citizen, but her dark hair and skin color consistently influence how the world perceives her.

As a major sector of racist remarks and a common reinforcer of discriminatory beliefs, these racial stereotypes can be constant reminders that race remains a source of division between people everywhere. From joking among friends to malicious statements meant to cause pain and exclusion, the ways in which stereotypes affect minority individuals are diverse.

Being Hispanic, Brignoni is often misidentified as Mexican; she hears comments that reflect stereotypes about Mexicans and witnesses the stereotyping of Spanish-speaking countries.

“Mexico and Puerto Rico are two different countries. I always have people ask me if I speak Mexican, or if I like tacos, [but] there’s a distinctly different culture between Puerto Rico and Mexico,” Brigoni said. “They are not even close.”

Brignoni feels that spreading and reinforcing this kind of inaccurate stereotype can put a negative lense over how people view each other.

“Stereotypes lead human beings to make assumptions about other people,” Brignoni said. “So that would be my biggest caution, not a specific stereotype or phrase, but more so just being aware of how stereotypes can influence your thinking about other people and how far off-base they actually can be.”

These kinds of stereotypes have become embedded and subsequently created a ground for psychological and structural violence against minority groups. Communications teacher Sohail Jouya – who is of Persian and Kurtish ancestry – comments that his skin color places him in a group strongly tied to racial stereotypes.

“Islamophobic racism has been a central component of life for most Muslims,” Jouya said. “Tropes of being violent, irrationally aggressive, and a threat is oftentimes coded onto people who look like me.”

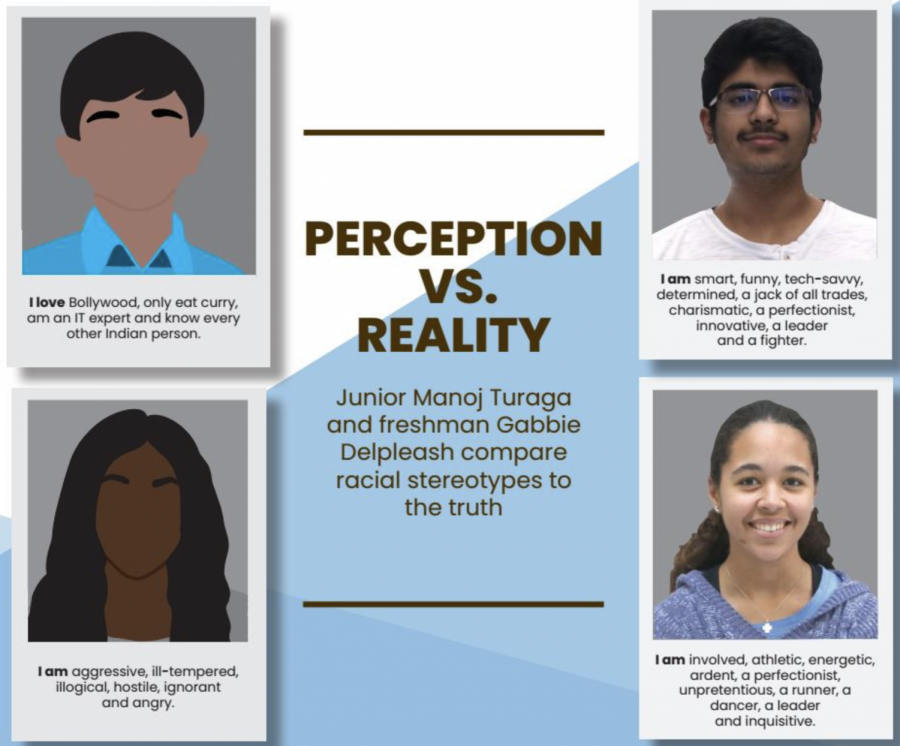

Unfounded and irrational stereotypes are exacerbated even within school; freshman Gabby Delpleash has witnessed school faculty make comments that perpetuate inaccurate assumptions.

“Today specifically, one of my teachers insinuated that black people couldn’t swim,” Delpleash said.

Other teachers seek progress toward racial acceptance. Brignoni uses her class as an opportunity to open the floor to discuss these kinds of stereotypes. She’s come to the conclusion, after years of teaching, that people’s natural tendencies to judge often evolves into the harmful negativity that feeds malicious behaviour.

“It’s a natural inclination for us to want to categorize people, but unfortunately stereotypes have gotten so out of hand that most of them have become negative,” Brignoni said. “And we talked about it in class quite a bit. They started to try and come up with stereotypes that they’ve heard, and none of them were really very nice.”

Jouya, on the other hand, believes that mere discussion about stereotypes won’t produce any solutions for resolving these issues, but rather that an in-depth anti-racist training and curriculum is necessary for improvement.

“I’m actually not always sold that discussion of stereotypes themselves are particularly fruitful enterprises,” Jouya said. “I do believe that serious anti-racist training for employees and students would be a great idea and is long overdue.”

An awareness of racist behavior that would be brought about through such training would actually be able to resolve many instances of racism that happen in the educational sphere, according to Jouya. It would allow for those issues to be stopped before they become more of a problem.

“We’ve seen countless stories of white undergrads getting kicked off campus for using racial slurs, wearing blackface, and a number of other racist gestures,” Jouya said. “I can’t help but think that a number of those incidents could have been preemptively diffused by even the slightest of racial awareness training in K-12 education.”

However, stereotypes don’t always result in hateful comments. Junior Manoj Turaga and his friends commonly joke about being him being a “tech savvy Indian” – a stereotype often associated with his race, but one that accurately describes his own talents. Under these circumstances, he doesn’t see the harm in joking about it.

“I don’t think it’s bad; I like to take a joke. And certainly, I’m a different kind of person than most people in the world – I don’t get offended by things at all,” Turaga said. “Certainly, the things that people say to me, some people will get offended [from]. And I’m not the person to judge whether it’s racism or this stuff is okay; that’s up the person [the comments are directed at].”

Turaga notes that these comments sit differently when they come from strangers, though he recognizes that people don’t always have harmful intentions when joking about stereotypes.

“It is kind of weird, but they usually mean no harm. I don’t mean any harm whenever I do things [like that], and I hope that’s the case with them too,” Turaga said.

Brignoni describes how they can be a reflection of ignorance about a race’s history and culture.

“I think some people don’t realize what some stereotypes are based on,” Brignoni said. “They may go back to a time of war or time of oppression for certain people. Also, I think just people [say things] they’ve heard and they don’t realize the effect that it has on people.”

For instance, she has seen stereotypes represent misinformation.

“I’m surprised [by] how many people don’t realize that Puerto Rico is a Commonwealth of the United States, meaning that I am a born citizen,” Brignoni said. “Whereas some people will sometimes be like, ‘Do you have a green card to be in America?’ and I’m like ‘No.’”

Many minorities like Turaga exchange joking stereotypes as lighthearted fun, and others like Brignoni opt not to use them at all.

“You can make a heck of a lot of funny jokes without stereotyping somebody or at the expense of someone else’s culture,” Brignoni said.