Students and families take different avenues to gain U.S. citizenship or residency

Students and families who have immigrated maintain their roots while embracing opportunities of the U.S.

October 22, 2017

With the recent discourse over the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program or DACA, conversation about immigration has been reignited. An avenue for attaining residency, the DACA program is specifically for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.

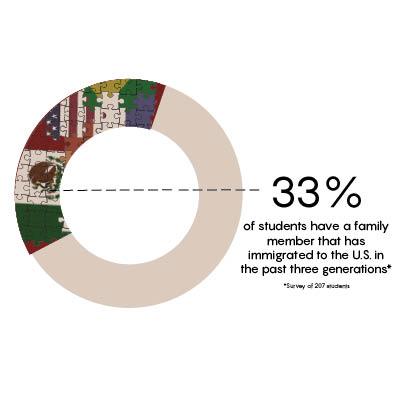

However, more and more people have been puzzled about how the immigration process works overall, as well as the different steps immigrants can take to become legal residents or citizens. At Mill Valley, students and their families have a diverse range of such experiences and paths.

For senior Carlos Niño and his mother Anabell Hernandez, who immigrated to the U.S. in 2001, the decision to pursue citizenship was made out of necessity.

“There is not a lot of opportunity [in Vela Cruz, Mexico]. The insecurity is just incredible,” Hernandez said. “Over there, I have family that never returned home.”

While Hernandez has become a citizen through marriage, Niño and his sister are a part of DACA. Niño is a part of the program due to the convenience of continuing the process.

“Since my mom got citizenship, I benefit from that,” Niño said. “But my sister has to wait through her whole DACA process to get citizenship.”

The main benefits the DACA program provides are a social security number and medicare to recipients. While Niño and his sister can also be employed, have a driver’s license and attend college, they cannot vote or travel outside of the U.S..

Those with visas, however, are able to enter and leave, but are still not considered permanent residents. Immigrant visas (including employment, student and family visas) enable the holder to apply for a green card, which allows permanent residency. After five years, a green card holder is eligible for naturalization, or legal citizenship.

Obtaining visas was the path that junior Ciara Pemberton’s parents sought when emigrating from England for work in 1998. After receiving work visas and eventually green cards, Ciara’s mother, Heather, obtained citizenship in 2014 to prevent her eldest daughter, Niamh, from taking the naturalization test.

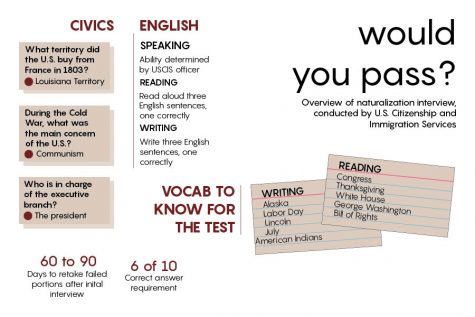

After months of Ciara and the rest of her family helping her prepare, Heather was able to pass the test, which included an interview and ten civics questions, and officially gained citizenship.

“I was super proud,” Ciara said. “I knew she had worked hard. She had been studying for a while and then she finally got it and was really happy too.”

Like Ciara’s parents, Spanish teacher Edith Paredes, originally from Paraguay, also seized the opportunity to come to the U.S. to further her career opportunities. She attended the University of Kansas and was able to pay in-state tuition due to the Kansas Paraguay Partners program and received a student visa and then a green card.

Like Ciara’s parents, Spanish teacher Edith Paredes, originally from Paraguay, also seized the opportunity to come to the U.S. to further her career opportunities. She attended the University of Kansas and was able to pay in-state tuition due to the Kansas Paraguay Partners program and received a student visa and then a green card.

“I just needed five years of being a green card holder to qualify for citizenship, but I went longer. I didn’t want to give up my citizenship [in Paraguay],” Paredes said. “I was a resident for about seven or eight years and then I applied for citizenship.”

Although Paredes and Heather eventually chose to undergo the naturalization process, some families have opted to remain citizens of their birth countries. Senior Durga Jambunathan is a native born American, but her parents immigrated together to the U.S. in 1993 for job opportunities and decided not to pursue naturalization.

“[My parents] didn’t want to give up their Indian citizenship because that’s a big part of who they are,” Jambunathan said. “[So] they’re still on their visas.”

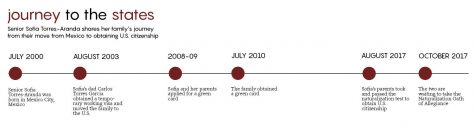

However, senior Sofia Torres-Aranda and her family, after having lived in the U.S. on a green card for five years, are in the process of becoming citizens.

“After having the green card, we applied for citizenship,” Torres-Aranda said. “It [was] more than six months before we got the notice that they could go take the test. [My parents] passed it, so they’re just waiting to get the letter in the mail that tells them they can go take the oath.”

Taking the test

Because of the diversity of citizenship statuses in the community, some teachers, including social studies teacher Cory Wurtz, have taken it upon themselves to educate students about the process through the administration of a mock naturalization test.

While Wurtz does not take this test for a grade, he administers it with the goal that his students can learn and take something away from it.

“If you’re learning a second language and you’re having to learn all about U.S. history when you haven’t lived here all your life, then it’s more eye opening and maybe [my students] don’t take their citizenship for granted as much, that’s kind of what I’m hoping,” Wurtz said.

After seeing her stepmother Marilei Rothgeb attain citizenship in 2015, junior Lauren Rothgeb realized the difficulty of the process.

“[Marilei] had to learn all these facts for the test and go through such an elaborate process addressing each little thing,” Lauren said. “I remember when she was studying for the test, [there were] things I didn’t even know and I’m a natural born citizen.”

Similarly, Paredes started her naturalization process in 2003, moving from a student visa to a green card before taking the citizenship test. Paredes considers herself lucky to have had the opportunities she received in regards to her citizenship status.

“Many people I know still don’t have legal status,” Paredes said. “Many have had to marry out of convenience to get that status, [so] I was very lucky to be in the path I was, having a college education.”

Keeping the culture

Despite planting roots in a new country, these families have all found ways to stay in touch with their culture. Paredes continues to pass on her Paraguayan heritage through speaking Spanish at home and sharing her cultural knowledge with her children.

“Their education, their values, our religion, all the things we do at home [are] pretty much as if we were in Mexico or Paraguay,” Paredes said.

Hernandez also emphasizes values and lessons learned from her experiences, despite the difficulty in navigating between cultures.

“I didn’t want [Niño] to forget his roots, but I wanted him to integrate, to adapt to this country because it is his country now,” Hernandez said. “I want him to value every single thing [and] work hard.”

While culture is easier to stay connected with, maintaining relationships with family members scattered around the world can prove to be more difficult. Ciara, whose extended family resides in the U.K., often feels the struggle of keeping in touch with family.

“It’s definitely not easy,” Ciara said. “I envy my friends who can just go visit their grandma or grandpa every weekend.”

While the Pembertons visit their family every other summer, the distance between the two sides of their family in the U.K. presents a challenge.

“When you get there, you’ve got such a short amount of time to connect with everybody,” Heather said. “Because my family lives in England and Kieran’s family lives in Ireland, we take a week at each place and it’s not enough time really to catch up.”

Similarly, Torres feels the pain of the distance between her and her extended family in Mexico City, Mexico.

“Sometimes it can be kind of sad because I feel like they don’t actually know who I am since I left when I was three,” Torres said. “But it gives me something to look forward to.”

Due to his inability to leave the country as a result of his DACA status, Niño values the little things when it comes to family interaction.

“I don’t have the chance to see [my family], but when I talk on the phone I try to make it last,” Niño said. “I try to ask every question [and] cherish every moment I have.”