Students share how society can embrace neurodiversity

Neurodivergent students elaborate on the triumphs and struggles surrounding their diagnoses, as well as societal effects

April 27, 2022

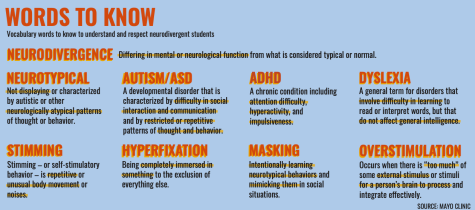

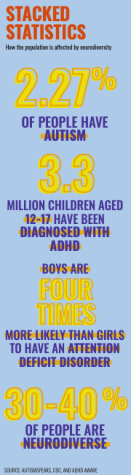

Neurodiversity describes the wide variety of ways that a person’s brain and thought processes can develop. Neurodivergent is an umbrella term for a wide variety of diagnoses: ADHD, autism/ASD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s syndrome, OCD, and those identified as gifted. While a neurologically diverse world can offer many benefits, some still don’t see this. Mill Valley only represents a small microcosm of the world, but the school educates many neurodivergent teenagers with unique experiences. These students share their experiences in hopes of creating a world that further values neurodiversity.

Growing up different

Growing up, many neurodivergent children feel different because they don’t learn in the same ways as their peers. This affects these children in a wide variety of ways including socially and academically.

Senior Hannah Hunter, who has been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), struggled when it came to socializing at a young age. Even though Hunter is now able to socially interact with many of her peers and won homecoming queen this year, social interaction didn’t always come easily to her.

Senior Hannah Hunter, who has been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), struggled when it came to socializing at a young age. Even though Hunter is now able to socially interact with many of her peers and won homecoming queen this year, social interaction didn’t always come easily to her.

“The diagnosis of my autism was in elementary school, my symptoms were that I didn’t want to be involved in things. I didn’t want to play with other kids, I wanted to be by myself in a little corner,” Hunter said.

Toward the end of middle school, senior Elisabeth Peters was also diagnosed with ASD. She found that by masking her neurodivergent traits, such as sensory sensitivity and differing social development, she began to lose her personality.

“You grow up being the weird kid, right?” Peters said. “You don’t know why. You’re just weird. You don’t have friends. You can’t connect. You’re just weird. So you try and learn how to be not so weird and then you lose yourself. It’s an incredibly difficult, incredibly challenging situation to be in, that you have to repress yourself on the most basic fundamental level in order to receive the things that other people around you receive by default.”

In addition to being autistic, Peters is also gifted. Gifted facilitator Inga Kelly, who was identified as gifted as a child herself, believes that as children grow up, their identity as a gifted student can become a burden.

In addition to being autistic, Peters is also gifted. Gifted facilitator Inga Kelly, who was identified as gifted as a child herself, believes that as children grow up, their identity as a gifted student can become a burden.

“I think one of the things that I am thankful for is that we are continuing to evolve what we know about why older students still need gifted services,” Kelly said. “I think there’s this conception all along that gifted kids will be fine. ‘Oh, those kids, they’ll be fine.’ And I think that that is true in some cases, but not all. And I think that anytime we know that somebody wants or needs something that will help them reach their potential if we have the ability to support that.”

Sophomore Ella Doyle has dyslexia and dysgraphia, which cause letters and words on a page to appear as though they are flipping and moving about the page. This makes reading and writing more time-consuming tasks for Doyle.

“I would always be really behind in reading and be really slow at reading, so I would be like put in the stupid reading classes and the lower level [groups] until they realized that I just need more time to read,” Doyle said.

Standards and stereotypes

Many different aspects of neurodivergence are commonly stereotyped or misrepresented in the media. Despite this, a growing awareness of neurodiversity has provided some opportunity for better representation.

Peters was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was young. For this diagnosis, Peters found representation in internet memes. However, when Peters looked for similar content after finding out she was autistic, the content was much more harmful. Luckily, she was able to find representation in other places.

“I was fortunate enough to have been introduced to some really good representation in what I would learn to be my special interest,” Peters said. “It was Overwatch, which is a video game published by Blizzard Entertainment. One of the characters that was really well known at the time was acknowledged as being autistic, and she was a really cool character. So I remember getting my diagnosis and being like, ‘Hey, I’m like her.’”

“I was fortunate enough to have been introduced to some really good representation in what I would learn to be my special interest,” Peters said. “It was Overwatch, which is a video game published by Blizzard Entertainment. One of the characters that was really well known at the time was acknowledged as being autistic, and she was a really cool character. So I remember getting my diagnosis and being like, ‘Hey, I’m like her.’”

On a more negative note, Kelly believes that the pressure put on students who are identified as gifted has led to misleading stereotypes concerning them.

“I think there are a lot of misconceptions about gifted kids. I think one of them is that all gifted students are like little robots that you program,” Kelly said. “They’re perfect and they’re rule followers and they love doing every single everything and they never need to rest or take a break or all those kinds of things.”

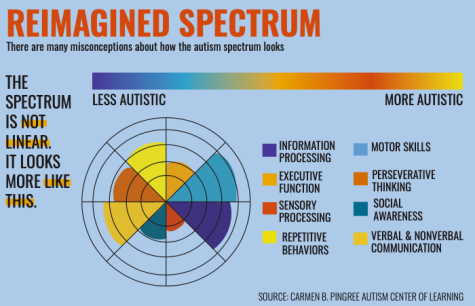

In addition to harmful stereotypes about giftedness, there are harmful ideas about ASD as well. Many terms try to put neurodivergent people into boxes when those boxes don’t really exist. This is why, according to Peters, ASD is best represented as a spectrum.

“In reality, it’s a very fluid thing,” Peters said. “The [autism] spectrum is represented by a rainbow radiant infinity loop because [autistic people are] not the same, but we’re different in the same ways.”

For junior Atticus O’Brien, who was diagnosed with ADHD, it is important to recognize that people are more than their diagnosis.

“I think people see people by their personality,” O’Brien said. “I think if you have ADHD that can play into your personality but I don’t think it necessarily defines who you are.”

Ending exclusivity

While the world may not become instantly inclusive, there are many things that the school can do to create an environment that fosters neurodiversity and inclusion.

Being both gifted and autistic, Peters has spent time in both the Voyagers (gifted) room and in other special education rooms. She feels that the environment for students in each room can be very different and hopes that this can be improved in the future.

“I sometimes feel like an inconvenience when I’m in the SPED room,” Peters said. “I have been able to see both sides of that coin. And there definitely is, it feels like, a lack of belief in the SPED room like, the walls there are starker. There aren’t very many motivational posters in the SPED room.”

For Kelly, it is important to recognize that no two students are the same and that each require their own accommodations.

For Kelly, it is important to recognize that no two students are the same and that each require their own accommodations.

“It’s other diagnoses that really influence how your giftedness exhibits itself,” Kelly said. “[No gifted students] are identical. And so I think unlike something that’s pretty straight forward, like ‘the student has dyslexia so you do this,’ if you say the student is gifted, there’s not one right way to educate them. It has to be responsive to that individual’s needs.

According to Doyle, English class is the most difficult with dyslexia, and there are small things teachers could do to help.

“I feel like they could tell English teachers that some people take longer to read stuff,” Doyle said. “With timed writings and timed readings, it’s going to take longer to piece together the words and not everybody can do the same thing at the same pace.”

Peters finds many terms used to refer to autistic people to hinder the ability to get accommodations, some of which being functioning labels.

Peters finds many terms used to refer to autistic people to hinder the ability to get accommodations, some of which being functioning labels.

“If you label someone as high functioning, they’re not allowed to be autistic,” Peters said. “If you label someone as low functioning, autistic is all they’ll ever be.”

Hunter believes that education can help lead to a better future, which the school is well suited to accomplish.

“One of the ways that the school can do this is to teach and educate more students who don’t have autism or who are not on the spectrum by educating more about autistic people so that [autistic students] can be more nice and kind,” Hunter said.