Teachers experience varied career paths

Before working at the school, teachers undertook various jobs similar and dissimilar to their content areas

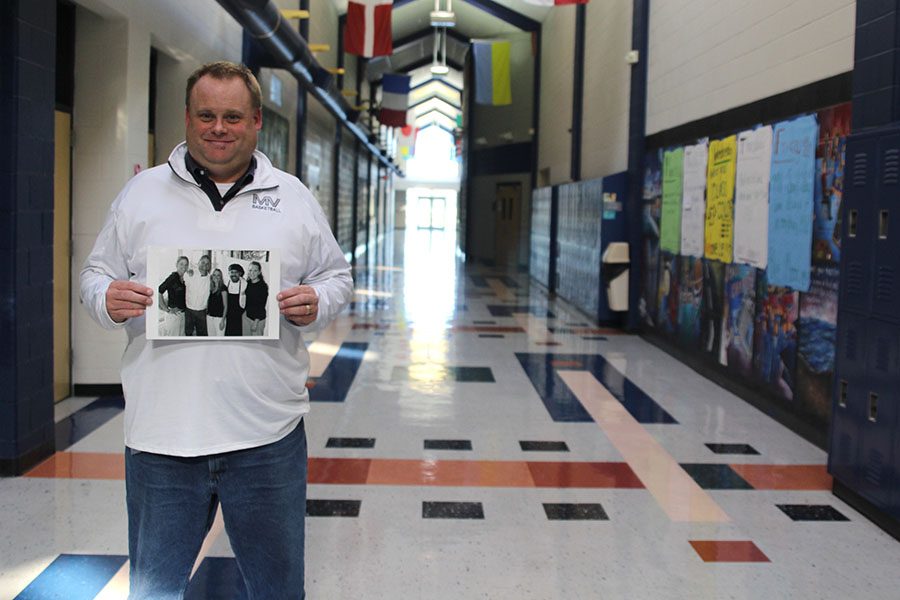

Holding up a photo of former coworkers from his 18 years of experience in the restaurant industry, math teacher Kevin Mosher stands in the main hallway. Mosher worked as a waiter, manager and executive chef before becoming a teacher in 2010.

February 3, 2018

Around 1993, math teacher Kevin Mosher works around a restaurant, first as wait staff during college, running the front of the house full-time, taking on the role of manager, and eventually working as an executive chef. He travels for a month and a half at a time, working up to 80 hours a week, before coming home to his family. Later, around 2010, Mosher finds himself teaching math at the school after having gone back to college to get a degree in education.

It’s a common assumption that most students, after graduating from college with a certain major, will have their career path laid out for them. However, in the cases of many teachers at Mill Valley, their initial careers were entirely different from their final teaching profession.

For example, speech teacher Annie Goodson, who received a degree in education, changed her career path after graduation. Goodson, who sponsors debate and forensics, worked as a director, actress and freelance comedy writer with Second City and iO theatres. She later co-founded her own theatre company, Mass Street Productions, with friend Willie Opper and wrote for the National Public Radio and The Onion.

Holding up her certificate of completion from the Second City Conservatory, speech teacher Annie Goodson poses with a few acting props. Goodson is a former professional actress, director and writer.

“After I graduated from K-State, there weren’t a lot of teaching jobs,” Goodson said. “Part of me wanted to go to law school, and part of me wanted to be a writer. I ended up going to Chicago, with the idea of going to law school, [but] I last-minute changed my mind and ended up auditioning for Second City.”

Like Goodson, science teacher Chad Brown began college with “the eventual goal being to get [his] degree in education.” However, for Brown, doing so “did not happen until many years later, due to getting some fantastic jobs.” Brown received his bachelor’s degree in physics, but ended up working as an accountant for a music shop and later, a database administrator for eight years in a law firm.

However, Mosher hadn’t anticipated becoming a teacher until years later. He had received his bachelor’s degree in business, although his various jobs in the restaurant industry led him to develop new skills, such as his time working as an executive chef.

“I’m not classically trained, so I was learning how to do [the job] while working it,” Mosher said. “It’s a different set of requirements from running a house or running the waitstaff. But it was really fun.”

It was the birth of his children, as well as the state of the economy, that “gave [Mosher] the push from what [he] was comfortable doing into something different.”

“I don’t know if I would have chosen it when I was 21 or … when I was in college for the first time,” Mosher said. “But as an adult, in my 40s, I feel [that] this is where I need to be, and this is where I want to be.”

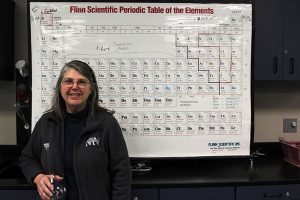

Science teacher Mary Beth Mattingly also had little intent to be a teacher when she had attended college. Mattingly originally worked as a lab chemist at Virginia Commonwealth University, studying enzymes and hormones.

While holding up a volumetric flask, science teacher Mary Beth Mattingly stands in front of a periodic table. Mattingly worked as a chemist for seven years after attaining her master’s degree before becoming a teacher.

However, after the birth of her sons, Mattingly decided to become a stay-at-home mom. Later, she returned to college and earned an education degree at the University of Kansas. Mattingly “enjoyed helping students when tutoring in college,” so when it came to teaching, she “kind of grew into it.”

Like Mattingly, the focus of Goodson’s past jobs directly relates to the content taught in her speech classes. However, Goodson did learn new skills from professional theatre that she now brings to the classroom.

“One thing we learned at Second City is that their motto is ‘yes, and?’” Goodson said. “[Because of this motto, I am] able to provide feedback for kids in a way that isn’t hateful or doesn’t make them feel crummy, by saying ‘yes, and let’s also do this’ or ‘that’s an awesome idea, let’s also do this.’”

Mosher’s experience in the restaurant industry also enabled him to utilize the basic skills that he now teaches everyday. This has given him an opportunity to demonstrate the importance of math to his students.

“One thing students ask is, ‘when am I going to use this?’” Mosher said. “I worked in an industry where you use it all the time. We measured everything. We weighed different things. We had to balance a checkbook, balance our inventory. It was something I was good at that I applied on a daily basis.”

However, while Mattingly applied the chemistry that she teaches to students in her laboratory work, she finds notable differences in the two careers, as lab work was “more of an internal path and atmosphere,” while “teaching is more consistent interaction with other people [and] trying to explain something on a theoretical level.”

It was that kind of interaction that led Goodson to return to teaching, as she found writing “kind of lonely.” However, Goodson continues to consider herself a writer. Thus, she encourages students to focus on their passions.

“Find the thing that is the best parts of what you are,” Goodson said. “Writing was part of that for me, and directing was part of that for me, but they weren’t enough. I did them for five years, and it just didn’t feel good after a while, and that’s because I missed teaching.”

And if a student doesn’t know what the best parts of them may be, it’s never too late to discover those or change, according to Mosher.

“It’s OK to go, ‘You know what? I want to do something different. I don’t want to be this, I want to be that,’” Mosher said. “I did it at age 40. And that was a scary proposition that late in life … but, it was the best decision ever. I really enjoy what I do.”

Because, as Goodson said, regardless of what those pursuits are, they may “find you to a different door or take you down a different pathway.”

“You’ll find out where you’re meant to be,” Goodson said. “So, don’t sell yourself short because you can’t major in that or it won’t make you money. Do the thing that makes you the best version of you.”