The science of sound

Anatomy teacher Eric Thomas, Physics teacher Ryan Johnston and Psychology teacher Kirsten Crandall explain how humans create and perceive sound

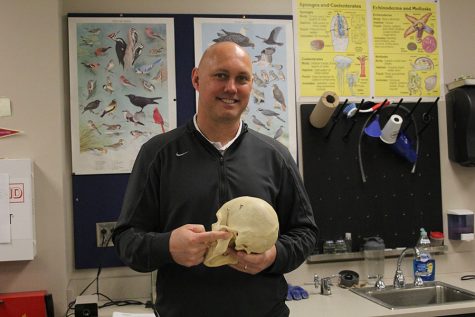

Hold a human skull, science teacher Eric Thomas points to the ear opening on Tuesday, Dec. 4.

JAG staffer: How do we produce sound?

Science teacher Eric Thomas: It starts with the diaphragm and the lungs. The diaphragm acts on the lungs and it [relays] pressure to either bring air into the lungs or exhale air out of the lungs. The same thing affects your vocal cords, so as you speak, air is pushed past your vocal cords and as you desire a certain sound or pitch, those vocal cords will lengthen or shorten to give you certain tones in your voice. Your tongue and your laryngeal muscles will manipulate that sound as it comes through your pharynx to be able to have inclinations and tones.

JS: What would happen if one of those parts failed to work?

ET: You know, a smoker has a raspy voice. In some cases, old coaches have a raspy voice. Two different reasons: for the smoker, it is a scarring of the vocal cords. So, if you can imagine taking a piece of grass and putting it in between your thumbs and making that sound, that high pitched sound, and then covering that piece of grass with wax, it wouldn’t sound the same. Or, blowing up a balloon when you were a little kid; you made sounds with the balloon like it was flagellating. If you were to coat the opening of the balloon with tar, it wouldn’t sound the same. With a smoker, when their voice changes, it’s usually because of scarring of the vocal cords or build up of carcinogens on the vocal cords and also too difficulty of forcing air through their vocal cords. An old coach who has had to talk over players or yell at a game, that’s usually a scarring of vocal cords. It is an overuse from forcing air so much that the vocal cords lose elasticity so it produces the same kind of hoarse, raspy sound.

JS: What about the role of your mouth, the tongue in particular?

ET: The preciseness is more directed with the tongue and the teeth. So the sound, it’s going to make and even your nasal passage, those things are going to influence what people hear but it is not going to influence the air as it passes up through the pharynx So, the inclination and the specific enunciation, those are more the tongue and the mouth. The nasally sound can be a structural issue with the nasal passage and the throat. All of those things are playing a role, much like a musical instrument; as you change the shape, you are going to change the sound as it is projected.

JS: So the throat, diaphragm, lungs and vocal cords create the noise and then the tongue shapes that noise?

ET: The shape of the vocal cords too will determine the sound as well. You sound like your parents because genetically you have the same vocal cords. That is why there is sometimes that one person in the family that sounds just like somebody else because their vocal cords are different from somebody else. So yes, the vocal cords, lungs and diaphragm produce pure sound but they do that because of genetics. Your vocal cords are shaped slightly different than somebody else’s.

JS: Why do you think producing and understanding sound is important to our modern lives?

ET: It seems like it is becoming less and less as people become more in tune with social media technology that we are seeing more and reading more. We are not emphasizing communication as much but certainly the tone of your voice in terms of communication and your ability to speak is how the world perceives you. So if you are a kind, warm person, often times your voice is going to reflect that and if you are a mean-spirited person a lot of the times the way you speak is also going to be affected. So, I think sound and your voice is how you are perceived and it also too gives people an idea of your past. You know, I have a slight accent that I think when people oftentimes hear that they understand that you are from somewhere else. Or when I hear it, I know that somebody’s from the same place as me. There’s a commonality there.

JAG staffer: What is sound in terms of science?

Science teacher Ryan Johnston stands next to a diagram explaining how sound can be created on Wednesday, Nov. 18.

Physics teacher Ryan Johnston: Sound is basically the vibration of some type of matter back and forth in a wave type fashion. Most of the time it’s in air, as far as we are concerned, but it can also travel through other materials like wood.

JS: If you were to describe a sound wave, what would it look like?

RJ: So sound waves themselves, as far as air is concerned, are areas of kind of compressed air and kind of not compressed air. It would just be back and forth and back and forth. That is not a very good representation for people to visualize, so a lot of the times we represent it as what’s called a transverse wave. [A transverse wave] is if you take a rope and go “wee” up and down, that’s what it looks like. That is how we represent it so people can understand.

JS: What is the speed of sound?

RJ: It depends on the temperature and some other things but it is about 345 meters per second.

JS: How would you approach teaching sound to students?

RJ: You have to start with waves first. I always start with the resonance tube, which is basically a tube that’s open on both ends and you stick it in a bigger tube of water and then you have a tuning fork and kind of go from there. It’s pretty neat. It resonates which is a fancy way of saying that everything lines up just right so it makes a big sound.

JS: What is something that you consider cool about sound?

RJ: I thinks it’s neat how you can make so many different varieties of musical instruments based on a few simple principles that you can teach in a few minutes. For example, the difference between the clarinet and the flute. They make different sounds, obviously, but a flute’s more or less two open ends and you can make pretty sounds come out of it. The clarinet, it only has one open end, essentially. You add the reed to it and it adds a whole other dimension to the sound. If you place different finger openings here and there, you can effectively change the length of the resonance or the length of the vibrating sound wave inside, which is neat. You can change the frequency that way.

JAG staffer: What is the psychology of interpreting sound?

Psychology teacher Kirsten Crandall: So, in order for us to interpret sound, it involves two different processes. It involves sensation and perception. To be able to hear, we have to be able to funnel sound waves in using our ears and then we need our temporal lobes to process that information and make meaning of the sound. Understanding what it is that we’re hearing exists exclusively in the brain.

JS: How does the ear process sound?

KC: The ear is set up essentially like a funnel, so your outer ear traps the sound in order to get it into the ear canal and then those vibrations, it’s all about passing on vibrations to different parts of your ear. It’s going to use a bunch of tiny little bones in the middle ear, including your eardrum, to pick up on those vibrations and then eventually send them onto the cochlea. The cochlea is made up of liquid and tiny gross little hairs and the way that the vibrations move the liquid will cause the hairs to move and how those hairs move is what sends information to our brain.

JS: Why would a sound annoy someone?

KC: It somehow interrupts our perception. So, our perception and our brain are just trying to make sense of our world and predict our world as best it can. If a sound kind of gets in the way of us focusing on something, or gets in the way of perceptual understanding of what’s going on, that would likely irritate us.

JS: How do people recognize voices?

KC: We actually have really detailed association areas in our brain allowing us to notice very small differences in sensory stimuli, specifically with telling people apart. We have a part of our brain that allows us to notice the subtle differences in someone’s face and in someone’s voice. The reason a lot of scientists would say we have that really keen ability to tell the differences is because we had to in order to form societies and we had to form relationships to form societies and communities and keeping our species alive so we have this ability to tell humans apart very quickly and very well using those association areas in the brain.

JS: Why do people choose to be nonverbal?

KC: You have plenty of people who take vows of silence as kind of like a meditative kind of thing to internally process everything but then you also have people who possibly didn’t develop those language skills if they weren’t around a language being spoken. Their brain isn’t going to know how to form that. They might make sounds but they might not be making an actual language sounds so that could be due to issues with areas in the brain, in the left temporal lobe, or it could be due to developmental reasons.

Interviews condensed and edited for clarity.