Understanding the significance of carbon footprints

With personal ecological footprints playing a small role in carbon emissions, individuals consider more significant methods of environmentalism

April 20, 2021

![]()

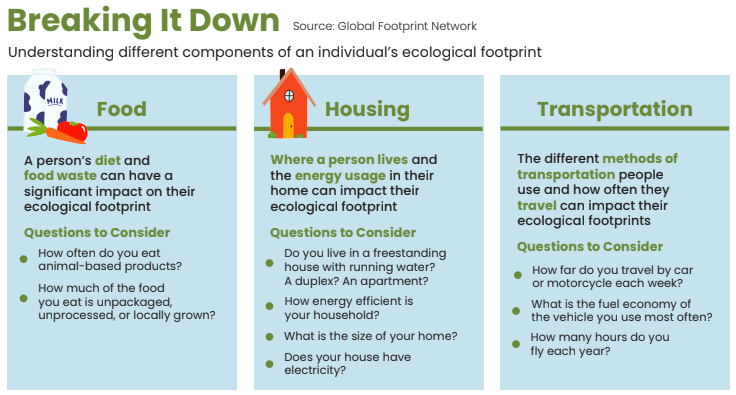

While environmental activism and awareness have grown increasingly prevalent throughout the past few decades – particularly across politics and social media – the popularization of environmentalism has still left many under-informed on the significance of their ecological footprints.

Wealthier communities, in particular, like Johnson County could benefit from a closer look at its disproportionate contribution to carbon emissions.

According to Dr. Paul Stock, the Associate Director of the Environmental Studies program at the University of Kansas, higher-income areas are more guilty of higher “production and consumption of consumer goods, higher rates of AC/heating use, higher rates of car usage, and other behaviors that are directly linked to higher carbon emissions.”

In light of increasing carbon emissions, sophomore Audrey Facer believes that both schools and individuals should spend more time spreading awareness about environmentalism, particularly on how individuals can reduce their personal impact.

“As a country, there are many things we could do such as limiting our unnecessary individual plastic packaging on food or other items, having school lunches locally sourced for each district, encouraging less car transport and using public or other transportation for little trips,” Facer said. “Everyone should recycle and compost and learn how to grow their own food.”

“As a country, there are many things we could do such as limiting our unnecessary individual plastic packaging on food or other items, having school lunches locally sourced for each district, encouraging less car transport and using public or other transportation for little trips,” Facer said. “Everyone should recycle and compost and learn how to grow their own food.”

However, Stock believes perspectives like Facer’s about the importance of one’s personal impact are largely fabricated by corporations dictating the meaning of environmentalism. He believes this is a barrier to substantial change even greater than factors like apathy or lacking education.

“The significance of high schoolers not comprehending their own carbon footprint is far more connected to corporate advertising and lobbying and media portrayals of what environmentalism should look like (that is, there should be a focus on individual behavior)… than anything else,” Stock said.

According to Stock, this emphasis on personal impact often takes attention off of industrial production, manufacturing and transportation – which make up roughly 75% of carbon emissions.

“We know that recycling and other individual and household behaviors do not go very far in reducing global carbon emissions on the level that are needed to enact actual change and yet we see towns and cities emphasizing those kinds of measures as triumphs,” Stock said.

This problem of misled environmentalism is echoed by sophomore Ella Doyle. Doyle “was surprised by how big of a carbon footprint [she] had” because, despite all she was doing to curtail her carbon footprint, her efforts had minimal results.

Rather than focusing solely on individual ecological footprints and making minor changes in everyday life, Stock believes a more effective approach would be to “broaden what we mean by day-to-day behavior to include learning how to become an engaged citizen that aims to talk with community leaders.”

Stock appreciates environmental activist Dr. Kathleen Dea Moore’s words of wisdom on the subject. When asked ‘What can one person do?’ Stock says she responds with “Stop being one person.”